When Sydney Fencl ’12 returned to Macalester for her sophomore year in 2009, the headlines were filled with news of a possible H1N1 flu pandemic. As the flu season heated up that fall, stores were filled with hand sanitizer, makeshift vaccination clinics sprang up everywhere, and more than 600 schools were closed against the contagion. By October, President Barack Obama declared the H1N1 outbreak a national emergency, and even Café Mac started allowing students to remove food from the cafeteria to control the spread of the virus.

“Our lives are so fast and furiously global, students realize that thinking about health is not just for medical professionals—it’s something all of us should be doing.”

—Devavani Chatterjea, biology professor

Keeping a careful watch on world events, not to mention the constant public service messages about coughing into your elbow, Fencl avoided the flu—but caught the fever. “I found the whole thing fascinating,” says Fencl, an anthropology major who watched with equal interest when Congress argued over the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act just as she was taking a politics of health class. “I think health is the most interesting thing you can study. Everything is connected to it.”

Thus inspired, Fencl spent a semester in Paris tracking the incidence of asthma in metropolitan France. Back home in Green Bay, Wis., the following summer, she used a Taylor Health Fellowship to create a childhood vaccination campaign aimed at boosting vaccination rates among new immigrants and skeptical parents. In her senior year, Fencl interned with the Minnesota Department of Health’s vector-born disease team, making telephone calls to track the progress of patients diagnosed with tick-born illnesses.

A decade ago, this kind of public health experience was reserved for graduate students, where community health training traditionally has been confined. But today Fencl’s wide-ranging study of global health challenges is an increasingly well-traveled path for Macalester students—especially those enrolled in the college’s relatively new concentration, Community and Global Health.

The interdisciplinary program encourages students to design their own six-course curriculum, take part in at least one internship or experiential learning opportunity, and come together in a senior seminar to share the lessons they’ve learned along the way. In the four years since the faculty approved it, the Community and Global Health Concentration (CGH) has become the most popular on campus, with more than 71 declared students. Biology, a top major chosen by CGH concentrators, is also Macalester’s leading major for the first time in more than a decade.

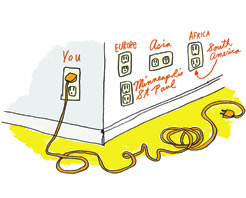

“There’s been this groundswell of interest among students who are becoming increasingly curious about public health both as a profession and as something that affects us all personally,” says Devavani Chatterjea, the biology professor who directs the Program in Community and Global Health. “Our lives are so fast and furiously global, students realize that thinking about health is not just for medical professionals—it’s something all of us should be doing.”

A trend 30 years in the making

Fueled by job forecasts predicting growing gaps in primary care, by the celebrity status of practitioners such as Paul Farmer (Partners in Health, Mountains Beyond Mountains), and pop culture films such as Contagion, student interest in public health is a trend that’s been widely reported at campuses across the country.

Fueled by job forecasts predicting growing gaps in primary care, by the celebrity status of practitioners such as Paul Farmer (Partners in Health, Mountains Beyond Mountains), and pop culture films such as Contagion, student interest in public health is a trend that’s been widely reported at campuses across the country.

Yet in spite of its ripped-from-the headlines feel, the roots of this trend go back at least to 1987, when David W. Fraser, M.D., then president of Swarthmore College, wrote “Epidemiology as a Liberal Art.” In this influential New England Journal of Medicine article, Fraser proposed that liberal arts colleges were the perfect training ground for the creative thinking and multidisciplinary approach it would take to solve challenges such as the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which had caught the medical world by surprise.

“The assumption was that we had effectively conquered infectious diseases, and that turned out not to be the case,” says Eric Carter, a medical geographer recently appointed to the Edens Professorship of Global Health, who will begin teaching at Macalester this fall. Though breakthroughs in antiretroviral therapy have significantly cut the mortality rate of AIDS, the World Health Organization estimates that fewer than half of the 15 million people who need the drugs have access to them. Health disparities like this make it clear that “medical answers only go so far,” says Carter, author of Enemy in the Blood: Malaria, Environment, and Development in Argentina.

“Some students who had no intention of studying the sciences have migrated that way because of their interest in public health.”

—President Brian Rosenberg

Fraser’s seminal article notwithstanding, the real turning point in global health came in 2000, says Christy Hanson, new dean of the Institute for Global Citizenship (see article on page 33), when a series of reports from the World Health Organization made a clear connection between poverty and poor health, and the threats they pose to economic development. “With non-communicable diseases, it has become clear that the West has been exporting some bad habits, from McDonald’s to smoking,” says Hanson, formerly chief of the Infectious Diseases Division for USAID. “And with infectious diseases transmitting on airplanes and across borders, it’s no longer a problem ‘over there.’ Good health is in everyone’s collective interest.”

By 2003, the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine was encouraging colleges to increase “access to education in public health” with the goal of creating “an educated citizenry” trained to tackle a multitude of growing challenges—from the health consequences of climate change to cutting infectious disease transmission. Macalester joined the discussion soon afterwards—at a series of academic conferences sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and the Association of American Colleges and Universities—as one of the first liberal arts colleges without an applied health sciences department to consider creating a public health curricular path. Since then, other private colleges such as Bates, Beloit, and Haverford have joined the effort, a trend that Hanson believes will only grow.

“Health is a key part of human development and many different disciplines can make a contribution,” says Hanson. “Anthropology students are great at exploring and understanding populations and cultural differences. Economists can weigh in about which approaches work best from a financial perspective. Scientists have a huge role to play in adapting technologies and monitoring disease.” She spent nearly 20 years working on international public health and infectious diseases before coming to Macalester.

“When you’ve got this student base of socially conscious young people looking for how to make a difference in the world, they see a home for themselves in public health,” says Hanson. “I think that’s what’s driving its popularity.”

Mixing passion with policy

Biology major Evelyn Balsells ’12 agrees that the wide net cast by public health helped fuel her interest in the Community and Global Health program. So did her passion for solving the hunger problems she’s seen in her native Guatemala. “I started off freshman year not knowing what to do with my feelings about fighting hunger,” says Balsells, who will continue her public health studies at the University of Edinburgh. “Fortunately, my classes in the concentration and my advisors’ help has shown me how I can channel this initiative in an institutionalized and focused way, so I can actually make a difference.”

Biology major Evelyn Balsells ’12 agrees that the wide net cast by public health helped fuel her interest in the Community and Global Health program. So did her passion for solving the hunger problems she’s seen in her native Guatemala. “I started off freshman year not knowing what to do with my feelings about fighting hunger,” says Balsells, who will continue her public health studies at the University of Edinburgh. “Fortunately, my classes in the concentration and my advisors’ help has shown me how I can channel this initiative in an institutionalized and focused way, so I can actually make a difference.”

That training started with a Taylor Health Fellowship that sent Balsells back for a summer to Guatemala, working with the Ministry of Health’s Institute of Nutrition. The experience helped her to see how “in public health you need to know policy language and how to speak to economists and ministers who want to know about cost effectiveness. You need to be fluent in all the ways stakeholders look at a problem.”

Back in Minnesota, Balsells began work with Open Arms, a nonprofit that prepares and delivers meals to people with chronic diseases. Recently relocated to Minneapolis’s Phillips neighborhood, the organization was looking for ways to introduce their work to the community. Balsells proposed a summer nutrition program that would serve neighborhood youth who rely on free and reduced-price school lunches.

“Health is a key part of human development and many different disciplines can make a contribution. Anthropology students are great at exploring and understanding populations and cultural differences. Economists can weigh in about which approaches work best from a financial perspective. Scientists have a huge role to play in adapting technologies and monitoring disease.”

—Christy Hanson

Working through the summer on a Chuck Green Fellowship, she met with nutritionists and social workers, studied USDA guidelines, and bumped up against a series of bureaucratic obstacles. “I found out there was a federal plan in place, but it’s not culturally sensitive, it’s not healthy, and children don’t like it. It was a lot of resources going to waste,” she says. “But I also learned why those things were true—the cost of transportation, food storage, farm subsidies, and the food politics behind it all.” One of the most important lessons she learned was that solving the problem would take patience. “One staffer told me that changing from serving sugary desserts to periodically serving apples had taken her five years,” she says. “That was a useful thing to know.”

Open Arms’ board of trustees approved Balsells’s summer nutrition program, adopting it as part of a five-year strategic plan. Last summer, Balsells’s classmate Emma Swinford ’12 implemented the program, serving more than 2,300 meals to kids in one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. “Turning Evelyn’s paper into practice was a huge learning experience,” says geography major Swinford. “You run into a lot of hang-ups you never thought about, so it was helpful to sit in on meetings at Open Arms and hear them figure out ‘how is this going to happen?’ or ‘who’s going to do this?’ or ‘how do you do the paperwork?’ ”

Using Mac’s Community and Global Health students as volunteers has been a boon to his organization as well, says Open Arms operations director Kent Linder. “We have a really lean staff and don’t always have the time to do investigative research or look beyond our current programs. So it was great that Evelyn could take her idea and run with it,” he says.

Though organizations like Open Arms are more accustomed to working with public health graduate students, “we’ve tried to give the students as much real-life experience as possible and not shelter them from the harder challenges we face,” Linder says. “The positive energy and excitement that undergraduates bring to this work is contagious; our friendship with Macalester has been a great exchange.”

Making connections, locally and globally

President Brian Rosenberg has been hearing the same from other public health partners who’ve recently worked with Macalester students. “They’re smart and they’re highly motivated, and they know what they don’t know,” he says.

President Brian Rosenberg has been hearing the same from other public health partners who’ve recently worked with Macalester students. “They’re smart and they’re highly motivated, and they know what they don’t know,” he says.

With the environment and global health among the top interests of incoming students, college administrators expected the Community and Global Health program to be popular. But they’ve been pleasantly surprised at the way in which students in the program—many of them women—have been encouraged to explore new disciplines and take classes in areas they may have otherwise overlooked. “Some students who had no intention of studying the sciences have migrated that way because of their interest in public health,” Rosenberg says, adding that anything that brings more women into the sciences is a “welcome development.”

Another asset for the Community and Global Health program is that its steering committee is made up of faculty in the sciences, social sciences, mathematics, and humanities—what Chatterjea calls a “truly interdisciplinary group, which is not necessarily true of other programs.”

The many local Mac alumni working in public health represent still another advantage for the program. Many of these alums have provided advice, spoken to classes about trends and career paths, and created internships in their workplaces. One of them, Melissa Kemperman ’99, an epidemiologist with the Minnesota Department of Health, says, “The liberal arts teach you to think broadly and that’s a really valuable skill,” especially as researchers explore the connections between health and environment.

Kate Lechner ’06 graduated before the Community and Global Health Concentration was created, but has returned to campus to discuss her experiences studying maternal health in Madagascar, working in the Peace Corps and for a nonprofit in Mali, and pursuing studies in public health and nonprofit management at the University of Minnesota. “Public health is constantly changing, so it’s necessary to be a lifelong learner,” she says.

Another recent classroom visitor was Mina Tehrani ’11, who came to Chatterjea’s senior seminar to discuss one of public health’s harder realities—its lack of funding. Tehrani worked with Somali refugee women at the East African Women’s Center until a budget shortfall forced the nonprofit to close its doors in February. “At first I was interested in public health as an intellectual pursuit, but working with these women and their families made it real and personal,” says Tehrani, who now works in refugee services for the Minneapolis Council of Churches.

Hearing from epidemiologists, immunologists, and community health practitioners in the classroom was an important part of his education, says Ethan Forsgren ’11, but so was seeing the work up close. A Taylor Health Fellowship allowed him to spend three months at the Minnesota Department of Health’s Office of Emergency Preparedness while working nights as a researcher in Hennepin County Medical Center’s emergency room. “The disparity between government offices and the ER gave me a more complete understanding of emergency medicine than I could have gained in either setting alone,” Forsgren says, adding that fellowship programs like this are critical to developing student interest and skills. Forsgren later started first responder organizations on campus and in Venezuela.

Creating more hands-on opportunities is clearly among the goals director Devavani Chatterjea has for the program. In January she and biology professor Liz Jansen and chemistry professor Rebecca Hoye visited Kampala, Uganda, where they explored the possibility of creating a global health course that would begin on campus and conclude with three weeks of fieldwork in Uganda. The course may begin as soon as fall 2012.

CGH concentrator and history major Mollie Hudson’12 joined Chatterjea on a research trip to Uganda last year, and has traveled several times to Tanzania—experiences that have prompted her to consider postponing medical school in favor of doing community health work in Africa. Her dream is to produce a series of radio programs for the women of rural Shirati, east of Lake Victoria, which would cover topics such as water- and food-born pathogens, maternal health, and malaria. Her dreams reflect one lesson she learned well from studying Community and Global Health at Macalester: “You don’t need an MD to make a big difference.”

St. Paul writer Laura Billings Coleman writes about health and education at ProBonoPress.org.

May 1 2012

Back to top