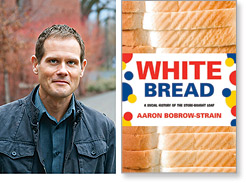

Aaron Bobrow-Strain ’92 is an associate professor of politics at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington, where he writes and teaches on the politics of the global food system. This is excerpted from his book White Bread: A Social History of the Store-Bought Loaf.

Reflecting back on 150 years of battles over America’s bread habits, five seductive dreams come up over and over again. Each one touched a deep chord in consumers’ relations to food, helping to usher in positive changes in the food system. And yet each one also underpinned more exclusionary and ambiguous outcomes. They are the dreams of purity, naturalness, scientific control, perfect health, and national security and vitality.

Each of these dreams rose to prominence because it crystallized a deep current of longing and anxiety—and thus galvanized action. All five endowed eating with seductive moral clarity: some foods were obviously good and some were clearly evil. On the surface, at least, who could possibly disagree with wanting purer food, more natural food, more abundant food made possible by science, healthier food that fought disease and weakness, or food that made the world a little safer and less hungry? And yet, each of these rousing visions of improvement framed the problems of society and the food system in dubious ways.

All five endowed eating with seductive moral clarity: some foods were obviously good and some were clearly evil.

The dream of purity animated important food safety activism, but also drove industrial and anti-industrial reformers alike to exclude and divide groups of people in the name of sanitation. Quests for purity created an enduring bridge between concerns about healthy diet and attempts to police against social “contagions” (like unwanted immigrants or alien ideas about health and nutrition).

Visions of naturalness, for their part, facilitated important critiques of industrial hubris and giant oligopoly food producers, as seen in the 1960s counterculture. But fears that the country had grown estranged from nature also enveloped food reform movements in nostalgia for an American Eden of independent, white, property-owning farmers. That nostalgia idealized female domesticity and local communities, glossing over the power disparities that always marked those realms. In the process, sentimental dreams of naturalness made it harder for well-meaning people to address inequalities in the fields, factories, and kitchens of industrial food production.

Narratives of scientific control typically stood opposed to the quest for natural harmony, but they were no less utopian in appeal. Large-scale food producers and ordinary consumers leaned breathlessly toward a future of abundance, leisure, and harmony made possible by speed, efficiency, and the conquest of nature. In the 1920s and 1950s this dream blinded many Americans to the hubris and shortsightedness of scientific control. In exchange for spectacles of efficiency, abundance, and control, people harnessed their sustenance to greedy corporations, embraced bread infused with chemical additives, lost sight of heterogeneous pleasure, cheered the remaking of world wheat farming into a petroleum-fueled factory system, and ignored the destruction of small-scale bakeries.

The dream of perfect health seeks something that is hard to dislike: life extension and bodily improvement. Nevertheless, even those achievements come at a cost. As seen in food movements from Grahamism to gluten-free, the quest for perfectly tuned bodies individualized and medicalized problems that might have been better addressed through social and political means. The quest for perfect health has also come with psychological costs for those who participate in it. With its fantasies of bodily control comes a relentless fear of deterioration and a sense that imperfect health reflects character weakness or moral failing.

Finally, dreams of food and national security and vitality help produce an anxious, Manichean geography. At times the perceived need to fortify “us” against “them” has legitimated attention to marginalized people’s demands for better bread, whether through wartime enrichment campaigns or postwar Food for Peace. But it has also nurtured an emergency mentality that propelled ill-conceived changes in the American diet and made alternative ways of organizing the food system appear dangerous and unpatriotic.

In sum, these five big dreams of food and society roused Americans to change their diets and food system, but often at a great cost. At root, each one of the five gave us the idea that good eating was a form of combat. But our alimentary trench war often had grave consequences for people on the margins or excluded from society…

In a time when open disdain for “unhealthy” eaters and discrimination on the basis of dietary habits grow increasingly acceptable, we might do well to spend more time thinking about how we relate to others through food and less about what exactly to eat.

Excerpted from White Bread: A Social History of the Store-Bought Loaf (Copyright © Beacon Press, 2012) by Aaron Bobrow-Strain. Reprinted with permission.

July 11 2012

Back to top