By Hillary Moses Mohaupt ’08

In December 1941, Shigeru Ochi ’49 was in the middle of his senior year of high school in south central Los Angeles when the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II. Soon after, in February 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal from the West Coast to inland “relocation centers” those deemed a threat to national security. Japanese Americans were swiftly targeted and interned.

A few months later, Ochi became one of the first Japanese Americans ordered by the federal government to Manzanar, an internment camp in the remote California desert. Government officials told Ochi—who’d been born in Los Angeles to Japanese-born parents—and the other young men who arrived early that if they helped construct the camp, they would be allowed to come and go as they pleased.

This turned out to be untrue, and eventually 10,000 people—mostly American citizens—were crammed into one square mile with extreme and harsh conditions: up to 110 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer, below zero in the winter, and always windy and dusty. By the war’s end, more than 120,000 people would be interned in a total of ten camps across the country.

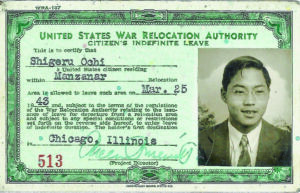

Ochi was held at Manzanar for one year and one day before being released into the custody of the Church of the Brethren, based in Chicago, in March 1943. The religious group was sponsoring people like Ochi who were eligible to leave the camp, and they helped him find a job in a Chicago model airplane factory, which allowed him to save enough money to pay for a year of tuition at Macalester.

“Mac was my first exposure to Minnesota,” Ochi says, recalling how the Twin Cities at the time, with its Scandinavian influences, were so different from where he grew up in south central Los Angeles, surrounded by Mexican and Japanese immigrants. Mac was the right fit for him, Ochi’s son Jim says, because of its academically rigorous yet welcoming environment.

Esther Torii Suzuki ’46, one of the namesakes of the current Lealtad-Suzuki Center for Social Justice on campus and the first Japanese American student at Mac, had arrived in 1942. Ochi remembers there being about a dozen other Japanese American students at Mac when he was there.

While Ochi had earned enough money for tuition, that didn’t cover all of college’s expenses. In exchange for a cot next to the coal furnace in the Bigelow basement, he stoked the dorm’s fire every morning at 5 a.m. and again after classes. To earn money for bread and peanut butter, he washed dishes at a nearby restaurant.

Ochi’s Macalester education was interrupted after his first year, when he was drafted into the Army in July 1944. He completed basic training at Fort Hood in Texas, where he met members of the 442nd regimental combat team, a segregated Japanese American regiment that became one of the most decorated teams in US military history. Ochi graduated from the US Military Intelligence School at Fort Snelling in St. Paul, where he took Japanese language classes before being sent to the Pacific theatre. He’d never attended any formal Japanese language classes as a child growing up in California, but spoke a mixture of Japanese and English with his parents.

In 1945, Ochi was sent to Hiroshima—where his family had lived for centuries—with the American occupational forces after the city had been leveled by the atomic bomb. He sent a letter back to Macalester that was printed in a December 1945 issue of the Mac Weekly, reporting on the dire effects of war he was witnessing. Miraculously, he tracked down members of the Ochi family—who had survived the blast but were suffering from radiation sickness, burns, and malnutrition—and delivered high-protein meals and other supplies.

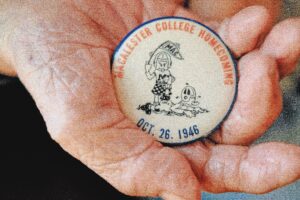

After being honorably discharged in October 1946, Ochi resumed his studies at Macalester—well into the fall semester. Despite his late arrival, he aced his courses that semester, going on to double-major in math and chemistry. “As far as I was concerned, math was one of the easier subjects, and a good way to get along,” he says. Thanks to the GI Bill, he was able to live in a dorm room like most Mac students. He would play active roles in the Macalester Christian Association and the Junior Toastmasters, and his name frequently appeared on academic honor rolls.

In the spring of his senior year, the Graduate Record Exam was administered nationally for the first time. A perfect score in its math section and his outstanding grades earned him a full scholarship to MIT for graduate school.

Later, his son Jim ’80 would marvel at Ochi’s academic success, especially during an era when there was so much anti-Japanese sentiment. Whenever Jim asked his father about it he would, in Jim’s words, “just shrug his shoulders and say, ‘I don’t know, I tried really hard and I got good letters of recommendation.’” The widespread standardization of the GRE may have also worked in Ochi’s favor. “For the first time ever schools had an opportunity to objectively evaluate applicants from throughout the country,” Jim says. “And I believe that’s how Dad got MIT’s attention.

Ochi and his wife Virginia raised their four children in New Brighton, a Twin Cities suburb a short drive from Macalester. He was an engineer at UNIVAC, one of the first computer companies in America, and later formed a startup with several other engineers called Comten that went public on the New York Stock Exchange in 1968.

Ochi was the first person in his family to attend Macalester, but he wasn’t the last. Six others followed him, including his younger sister, Midori ’48, who’d graduated from Manzanar High School while interned. A niece, Meloni Hallock ’70, serves on the college’s Board of Trustees. His sons Jim ’80 and Bob ’85 and grandson Derek ’12 all majored in biology at Mac, and all three became physicians inspired by Shigeru’s determination to receive an education. Bob also met his wife, Amy Shapiro Ochi ’85, at Mac.

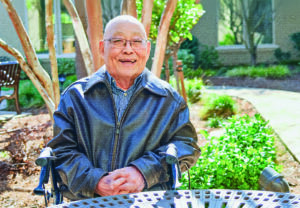

In 2019, Derek accompanied his grandfather to Ochi’s 70th Reunion. “He was so elated to go back to the place that provided him those opportunities and memories,” Derek says. “I could tell from the way Grandpa always spoke about Macalester that it was one of the most important experiences in his life.”

Now 101, Ochi lives outside Sacramento, in a memory care facility not far from several family members.

“My grandpa really set an example of pursuing an education even when it’s not the easiest thing to do. He had to face a lot of challenges,” Derek says. “He doesn’t come out and really talk that much about all the details of his story—he’s an open guy, but he’s very humble. As I learned more I realized that it’s important to take advantage of the opportunities you’re given. That inspired me to try to do the same.”

Hillary Moses Mohaupt ’08 earned a master’s degree in public history and is a freelance writer in the greater Philadelphia area.

August 18 2025

Back to top