By Collier Meyerson ’07 / Photo by Kevin Bernie

James A. Williams ’77, then a sophomore, enrolled in Professor Glen Wilson’s Voice and Diction class in the Theater and Dance Department. A so-called “tough” professor with a reverence for the classics, Wilson demanded his students learn how to breathe for the stage, and also, how to speak the King’s English. It was 1975, at the height of America’s Black Power movement, and while Williams was more interested in making art that reflected his experience as a young Black man, he felt motivated by his professor. “It was the desire to show you that I can do your stuff as well as you,” he says. “What I got from [Wilson] was discipline.”

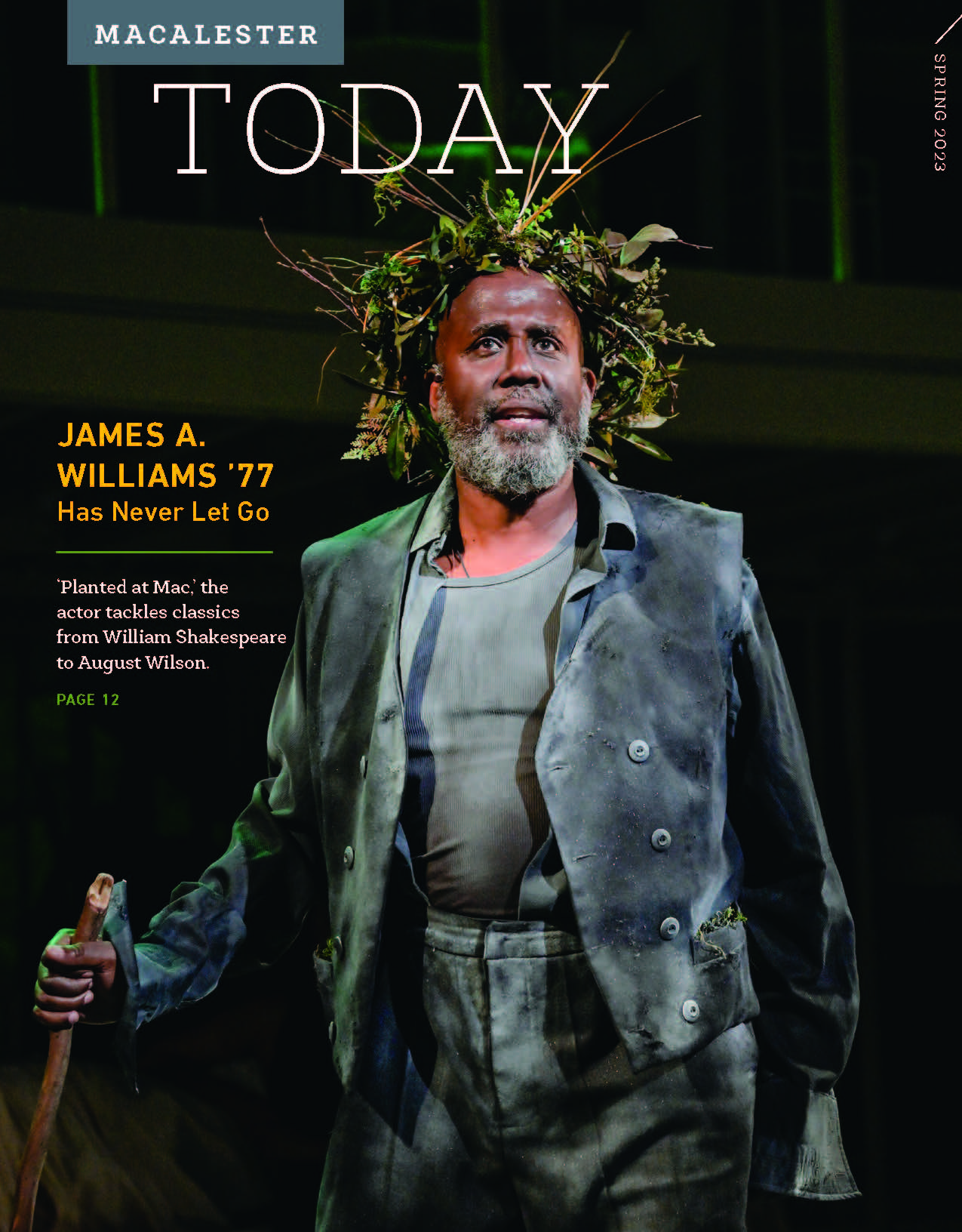

That theater class at Macalester laid the foundations for Williams’ powerful diction, voice, and his ability to command a stage—all techniques he would go on to employ nearly fifty years later as Lear for his most recent role in Marcus Gardley’s adaptation of King Lear with Oakland’s Cal Shakes theater in 2022. The play is a modern translation of the original, set in San Francisco during the 1960s in the city’s historically Black Fillmore District. Williams credits Professor Wilson specifically as his motivation for studying Shakespeare.

But this wasn’t Williams’ first time performing Shakespeare. Over the years, as a member of Minneapolis’ esteemed Guthrie Theater, he has played roles in its productions of King Lear and Romeo and Juliet.

And Williams’ accomplishments extend far beyond Shakespeare. He has held off-Broadway stints in Jitney and The Piano Lesson, two works by legendary playwright August Wilson. His commitment to community, a large part of his identity as an actor, has led him to leading workshops at Brown University, Colby College, and the International School of Kenya, among others. Minneapolis’ Star Tribune named him Artist of the Year twice.

For Williams, it all started at Macalester. “I never knew that I was a creative until I got into Macalester and got a chance to be one,” he says. “That’s what Macalester’s theater department did for me.” Williams elaborated on how the tutelage of Professor Wilson helped him see his potential. “You started out with Robert Frost, moved on to Gerard Manley Hopkins, and then a bunch of old dead white poets,” he continues. But at the end of the semester students were allowed to present works of their choosing. “I chose Paul Laurence Dunbar,” and for his final project he chose works from the Harlem Renaissance so that Williams could teach his professor something in exchange. “I wanted to hit him with voices he never heard before.”

It wasn’t only the professors at Macalester that helped Williams realize his dreams, but his cohort of theater students at the college. Jack Reuler ’75, who founded Mixed Blood Theatre in Minneapolis, asked Williams to be a part of the company. “From there,” he says, “another friend, Lou Bellamy, told me he was starting a theater in St. Paul and asked if I would like to be a part of it.” That theater, where Williams became a founding member, is Penumbra, where Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson got his start.

The 1970s were something of a renaissance for theater in the Twin Cities, and Williams found himself as its beating heart. “It’s one of the great joys of my life that one of the greatest writers to ever live wrote words for my mouth and that I got to say them first,” Williams says of August Wilson. “He picked me.”

Later, in 2004, the two would work together again. “He saw me do Two Trains Running and told his casting agent to have me submit an audition tape.” That audition tape landed Williams the role of Roosevelt Hicks in the world premiere of Radio Golf at the Yale Repertory Theatre, and, later, a run on Broadway. “I have been blessed to do the thing that people say can’t happen. No one goes from a regional stage in Kansas City to Broadway,” he says. “That’s what I mean when I say that Macalester taught me a lot of things.”

Part of what made Williams’ time so special at Macalester was that the college was piloting a program called Expanded Educational Opportunities (EEO), which brought students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, the majority of them Black, to study at the college. This program coincided with the country’s Black Power movement. “Discovering what it meant to be Black was such a new concept that everyone was trying to participate in it,” he says. Williams was coming from St. Louis, Mo., where he had been a bright and precocious kid. Because he was bullied, he dropped out of high school and spent his days holed up in a local library. A teacher in his school saw his potential and enrolled Williams in a program called Upward Bound which helped the young man secure a seat at Macalester, though he was admittedly a little lost.

“I didn’t know who I wanted to be and where I wanted to be,” Williams says of himself when he started as a first-year. “The seeds for my life got planted at Mac, and that’s why Mac is my heart,” he continues. “It gave me a determination to not give up. When I grabbed onto theater and acting, I was like Jacob in the Bible. I grabbed onto the angel and said ‘I will not let you go until you bless me.’ And I still haven’t let go. And I really don’t know if I ever will. There are times when I tried and it grabbed me back,” he says of trying to stray from theater. “So that’s my Mac life.”

Collier Meyerson ’07 is a writer living in New York.

April 28 2023

Back to top