by Sophie Hilker ’20

Every year, between the two weekends bracketing Halloween, writers, professors, artists, collectors, and readers gather for the World Fantasy Convention to celebrate creative works produced within the past year. Alongside reunion festivities, a select few attendees are nominated for and presented with awards honoring their work in categories such as Novel, Novella, Short Fiction, Anthology, Collection, and Artist. In the past, these prestigious awards have honored fiction produced by Ursula K. Le Guin, Stephen King, Ray Bradbury, Roald Dahl, Louise Erdrich, George R.R. Martin, and Neil Gaiman.

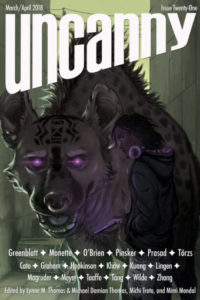

This year, Macalester alumna and English Professor Emma Törzs ’09 joined these ranks and was honored with the 2019 World Fantasy Award for Short Fiction for her story, “Like a River Loves the Sky,” published in the March/April 2018 issue of Uncanny Magazine. The story follows narrator Adrianna as she navigates grieving the loss of her mother’s memory, dreams in which she inhabits the consciousness of inanimate objects, and her roommate and longtime best friend, NPW — a taxidermist with an odd fixation for road-killed dogs — moving out. After reading this fascinating meditation on love and loss, The Words caught up with Professor Törzs to talk about genre, worldbuilding, and reading recommendations.

This year, Macalester alumna and English Professor Emma Törzs ’09 joined these ranks and was honored with the 2019 World Fantasy Award for Short Fiction for her story, “Like a River Loves the Sky,” published in the March/April 2018 issue of Uncanny Magazine. The story follows narrator Adrianna as she navigates grieving the loss of her mother’s memory, dreams in which she inhabits the consciousness of inanimate objects, and her roommate and longtime best friend, NPW — a taxidermist with an odd fixation for road-killed dogs — moving out. After reading this fascinating meditation on love and loss, The Words caught up with Professor Törzs to talk about genre, worldbuilding, and reading recommendations.

When I heard you’d won an award for fantasy, I think that shaped my expectations about what the story would look like more so than if the genre was fiction. When I heard “fantasy,” I (wrongly) assumed the subject matter would deal with a far-off world, but the world in “Like a River Loves the Sky” didn’t seem that far off. It seemed grounded in the reality we all face, but with a slight sense of the uncanny. Could you talk a little bit about outsiders’ interpretation of what fantasy means and how you view the genre? What drew you to writing fantasy?

Oh boy. Well, I don’t think you’re alone in your idea of what fantasy is (dragons! epic battles! names with random Ys and Xs!), and your question is an echo of a broader debate that often comes up about dividing lines between the “literary fiction” world and the “sci-fi/fantasy fiction” world. A generally-accepted set of definitions is that literary fiction values sentence-level prose and an intense focus on character, while genre/speculative fiction tends to value ideas, plot and entertainment over craft. But of course there are some unbelievably plotty “literary” page-turners and some stunningly-written well-structured “fantasy” novels. The lines are more blurred now than they’ve been in the past, thanks to a resurgence of the in-between genres like magic realism, new fabulism and slipstream, by writers such as Kelly Link, Karen Russel, Carmen Maria Machado, and George Saunders. And thank goodness! Labels are pretty boring.

Reading-wise I’m an omnivore and truly don’t prefer any one genre over another. In my own work I’m drawn to writing speculative fiction because it lets my ideas get huge but keeps the world of the story small and intimate. Some writer friends and I have an ongoing conversation about whether genre is a formal constraint or a formal release, and for me it is solidly both. I find it so fun and satisfying to fling the rules of reality wide open while adhering strictly to the rules of emotional truth.

Throughout the story, we learn what different iterations of love look like “outside of human terms” to the protagonist, Adriana. What does “love outside of human terms” mean to you?

More than once I have found myself googling “Does my cat love me?” in an effort to address this exact question, and I wrote this story partially as an attempt to imagine my way into a kind of answer — but the truth is, I think it’s fundamentally unanswerable. The idea of “love” is a human concept, created by human consciousness, so to imagine a “love outside of human terms” is a paradox in and of itself. To imagine love is already to be operating within human terms. I find it comforting, however, to try and de-center my human consciousness when I think about our world; for example, climate change terrifies me, but only because I’m human. If I could think like a rock, probably I’d have no fear. (Do I think rocks think? Well, “to think” is a human term that centers human consciousness, so we’re back at the beginning.) One of the reasons I write fiction is to explore these questions that have no easy answer, or perhaps have an answer than cannot be explained but can be felt.

As a soon-to-be-graduated senior I was wondering, how can I get Adriana’s job? Is this a real job? How did you come up with such unique jobs for your characters?

Adriana’s is a job I learned about while visiting a great little thrift store in Golden Valley called Empty the Nest. They have a home clean-out service where you pay a flat fee to have everything taken out of a home, often after relatives have died and left their houses full of pure stuff. It’s one of those details I mentally filed away to pull out when needed. I also have a literal file on my computer called “JobsForCharacters” where I keep track of interesting jobs I hear about (or not-so-interesting: I’m looking at it now and one note reads, “Something in an office — what do people do in offices?”)

What are some other great fantasy works and authors we should be reading?

Oooh! Don’t get me started. On the shorter side of things, I’d recommend anything written by Ted Chiang, Kelly Link, Lesley Nneka Arimah, Sofia Samatar, Charlie Jane Anders and Carmen Maria Machado — you can find a lot of their short stories online. In terms of novels I’ve loved in the past year or so, I suggest Helen Oyeyemi for her crackling, cackling prose and plots that can only be described as “bananas”; Circe by Madeline Miller for a fantastic, page-turning twist on the Odyssey; Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy for heartbreaking, sensual magic inspired by Russian mythology; N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy for a masterclass in worldbuilding; and Tamsyn Muir’s Gideon the Ninth for lesbian necromancers in a gothic space castle. I also have a huge soft spot for Leigh Bardugo’s enormously fun Y.A. Grishaverse series.

Oooh! Don’t get me started. On the shorter side of things, I’d recommend anything written by Ted Chiang, Kelly Link, Lesley Nneka Arimah, Sofia Samatar, Charlie Jane Anders and Carmen Maria Machado — you can find a lot of their short stories online. In terms of novels I’ve loved in the past year or so, I suggest Helen Oyeyemi for her crackling, cackling prose and plots that can only be described as “bananas”; Circe by Madeline Miller for a fantastic, page-turning twist on the Odyssey; Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy for heartbreaking, sensual magic inspired by Russian mythology; N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy for a masterclass in worldbuilding; and Tamsyn Muir’s Gideon the Ninth for lesbian necromancers in a gothic space castle. I also have a huge soft spot for Leigh Bardugo’s enormously fun Y.A. Grishaverse series.

Would you ever teach a class on fantasy/do you incorporate fantasy into your classes that don’t explicitly center on the genre? How does fantasy interact with other genres? What do we get from fantasy that we can’t get from any other form of media?

I often do teach speculative fiction. In fact, I think it can be especially instructive in creative writing classes, because with genre fiction it’s sometimes easier to isolate certain authorial choices in order to see what the author is trying to do. The genre stories I teach have a lot of the hallmarks people may associate with “literary” fiction: deep attention to sentence-level craft, subtle and considered use of language and structure, multiple levels of meaning, multi-layered character development, etc.

I often do teach speculative fiction. In fact, I think it can be especially instructive in creative writing classes, because with genre fiction it’s sometimes easier to isolate certain authorial choices in order to see what the author is trying to do. The genre stories I teach have a lot of the hallmarks people may associate with “literary” fiction: deep attention to sentence-level craft, subtle and considered use of language and structure, multiple levels of meaning, multi-layered character development, etc.

I’m also a huge worldbuilding nerd and think learning about worldbuilding is equally important in realistic fiction as it is in the fantastic, in no small part because it helps us see how we interact with power in subtle, fascinating ways. I definitely dream about teaching a worldbuilding-centric class someday.

If you could live in any fantasy world, which would you choose and why?

Any of my students could probably tell you that my love for the Harry Potter books is unstoppable, unreasonable, unhideable. I was ten when the first book came out and over twenty years later I’m still waiting for that owl.

Would you live in the world you created in “Like a River Loves the Sky”?

I would absolutely like to briefly inhabit the consciousness of an apple or a river or a rock! I would not like to be surrounded by ghost dogs.

The Words extends a huge thank you to Professor Törzs. Be sure to congratulate her if you see her around, and check out “Like a River Loves the Sky” for a fantastic fantasy read.