Kazakhs of Mongolia

Contact

Laura Kigin, Department CoordinatorCarnegie Hall, Room 104 651-696-6249

651-696-6116 (fax)

kigin@macalester.edu

facebook instagram youtube linkedin

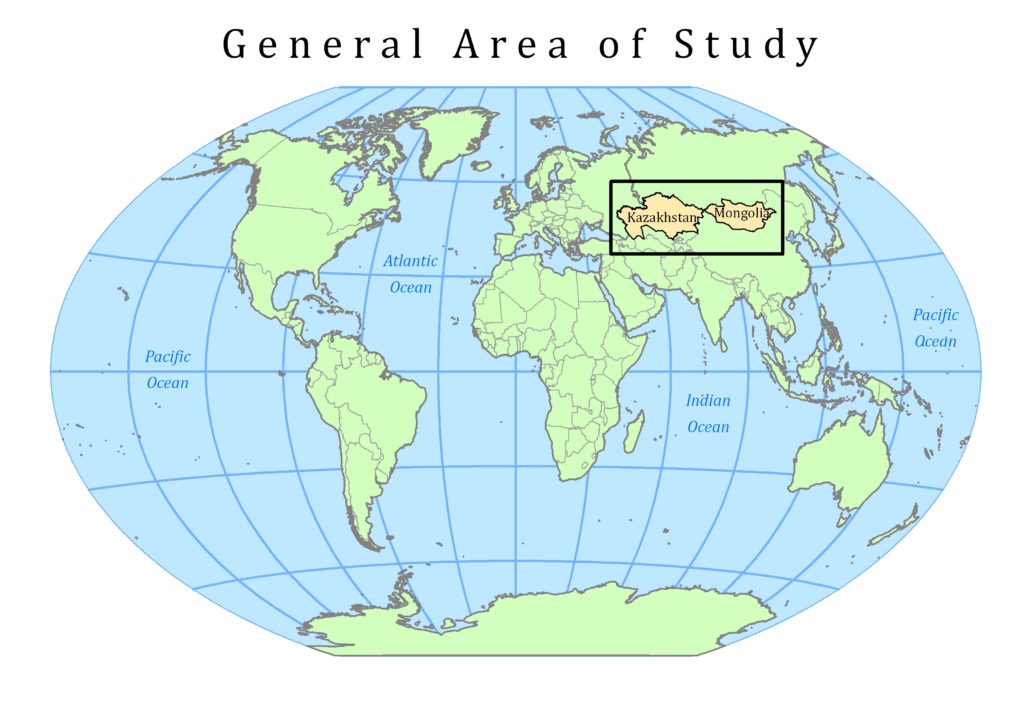

Geographers and anthropologists have long investigated the causes and consequences of migration from multiple spatial and temporal scales. In 2004, Holly Barcus and Cynthia Werner initiated a project in the western aimag of Bayan-Ulgii, Mongolia to better understand the on-going migration of Mongolian Kazakhs between Mongolia and Kazakhstan during the transition period between 1991 and 2010. During this period, Mongolia shifted from a communist to a democratic form of governance and from a command to a capitalist economy. This period also witnessed a rapid and important change in the freedom of movement both within Mongolia and across borders. One of these migration flows is comprised of Mongolian Kazakhs migrating to and from Kazakhstan during this period.

This website provides an overview of our work during the 2004-2010 period and the people who have helped us understand the dynamic relationships between gender, economics, identity, and geo-politics that shape the complex decision-making processes and outcomes of transnational migration in this region.

The Mongolian Kazakhs

Where do the Mongolian Kazakhs live? Our study site in Mongolia – a brief geographic overview

Mongolia is a landlocked country wedged between two regional giants – Russia and China. At the time of our study, it had a population of nearly 2.8 million people with a population density of less than 2 people per square km. Mongolia is very sparsely settled. While nearly 1 million Mongolians were living in Ulaanbaatar, the remaining 1 million were dispersed across the country.

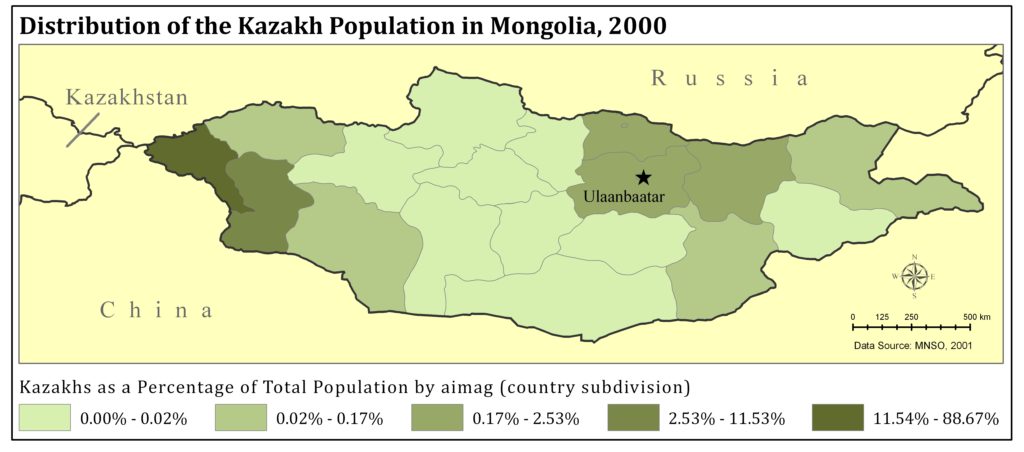

The Kazakh population is largely clustered in the far western province of Mongolia, Bayan-Ulgii Aimag, with the second and third largest clusters in Hovd Aimag and Ulaanbaatar. Our research is predominantly associated with Bayan-Ulgii (2006, 2008, 2009), although during the summer of 2006 we also conducted interviews in Hovd Aimag. Bayan-Ulgii is located in the Altai Mountain range and has the highest average elevation in Mongolia. The soum center of this arid and mountainous province is Ulgii, a town of approximately 30,000 people. During the summers of 2006, 2008, and 2009 we conducted interviews in Ulgii and in several rural locations across the province.

Who are the Mongolian Kazakhs?

The Kazakh people are the largest ethnic minority in Mongolia. Numbering over 100,000 in the 2000 Census, they comprise the largest ethnic minority in Mongolia, although only 4% of the total population. The Kazakh population is concentrated in the western province of Bayan-Ulgii, a region physically separated from Kazakhstan by a 47-60 km mountainous stretch of Chinese and Russian territory. Documented Kazakh migration to Mongolia begins in 1840 with many migrants arriving from areas now Western China. Records suggest that in 1905, there were 1370 Kazakh households, increasing to 1,870 households by 1924 (the year Mongolia adopted socialism). By 1989, the Kazakh population grew to approximately 120,000 individuals.

Before the fall of the USSR, few Mongolian Kazakhs had ever visited the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, but in the post-Soviet context the creation of new nation states and national borders, relaxation of restrictions on movement and opening of borders between east and west, new population movements have emerged.

The Kazakhs of Mongolia are culturally and ethnically different from Mongolians with language and religion as the two primary cultural markers. The Kazakh language belongs to Turkic family of languages, and is the dominant language in Bayan-Ulgii. During the study period, local schools taught in either Mongolian or Kazakh (this has since changed). Mongolian is the language of inter-ethnic communication and official language of government and business. The Kazakh population is predominantly Muslim. Although the majority consider themselves Muslim, a small but growing proportion practice basic Muslim tenets of Namaz and fasting during Ramadan.

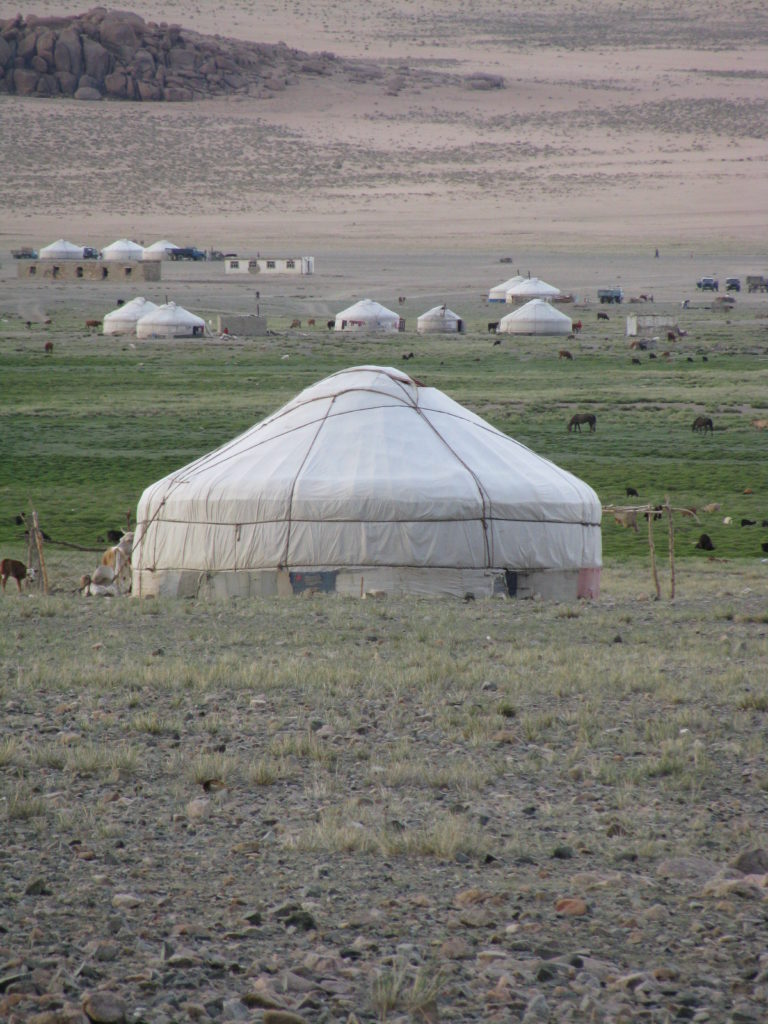

Mongolian Kazakhs are traditionally semi-nomadic pastoralists, herding sheep, goats, yaks, camels and horses. The nomadic economy is strongly influenced by traditional gender roles – men herd, women cook, care for children and prepare textiles. Under socialism in Mongolia (1924-1989), the pastoral economy was collectivized and modern education, health care and public infrastructure including social welfare policies were implemented.

During socialism and even more rapidly since 1989, there has been a gradual transformation of gender roles and gender relations. While the pastoral economy plays an important role in the economy of Bayan-Ulgii, trade and tourism have also emerged as the border crossings between Mongolia and China and Russia have increased and as air transport and tourism have increased in Mongolia more generally.

What does it mean to be semi-nomadic?

Physiographically, Mongolia and Kazakhstan are largely comprised of grassland steppe, although both countries also contain other eco-regions including deserts, mountains and forests. A limited amount of precipitation creates arid, non-arable pasture lands that historically have been utilized for livestock herding. Nomadic pastoralism has been the primary form of human subsistence for centuries. Politically, the Mongolian and Kazakh steppes were controlled by nomadic tribesmen until the late 17th century when they came under the influence of Chinese and Russian empires respectively. In 1920, however, Kazakhstan was incorporated as an autonomous republic of the Soviet Union and in 1924 Mongolia became the second communist country in the world. These political shifts significantly transformed cultural practices and economic structures within the two countries. The governments of each country sought to collective and sedentarize the nomadic populations under socialism. Government efforts were more successful in Kazakhstan, however, in Mongolia the government did not successfully collective the nomads until the 1950s.

Kazakh herding families in Mongolia today are considered semi-nomadic. For most herding households, this means that the household will move their herds, largely comprised of sheep and goats, although also containing variously camels, horses and yaks, to different pastures for each of the four seasons. Some households will move only two times, once in the spring to the summer pastures and again in the fall back to the winter pastures. Others will move up to four times, depending on the quality of the pasture in a given year. Most families return to specific pastures year after year with use of that pasture being passed down through families.

Why are the Mongolian Kazakhs migrating to Kazakhstan?

When the former USSR dissolved, and Kazakhstan declared independence, PRESIDENT Nazarbayev welcomed back the diasporic Kazakh community, including Kazakhs from Mongolia. When the USSR dismantled, 73 million people found themselves living outside the political unit that they viewed as their ethno-national homeland. Notable here were the Mongolian Kazakhs. Estimates suggest that between 50-60,000 Mongolian Kazakhs emigrated from Mongolia to Kazakhstan in the early 1990’s with possibly 10,000-20,000 returning by the early 2000s. Since 1991, Kazakhstan one of three countries to repatriate kinsmen living abroad (the others are Germany and Israel). While migration flows have fluctuated since 1991, over 71,000 Mongolian Kazakhs have migrated to Kazakhstan in the post-Soviet period.

Why do some Mongolian Kazakhs stay in Mongolia?

Our interviews and surveys indicate that there are many reasons why some Mongolian Kazakhs choose to stay in Mongolia, rather than to migrate to Kazakhstan. Results from our interviews suggest that individuals and families who are adapting well to Mongolia’s new economy are less likely to consider moving to Kazakhstan. This is age dependent, however. While successful middle-aged business owners and herders are relatively satisfied with life in Mongolia, their children consider attending university in Mongolia, especially Ulaanbaatar, or Kazakhstan. With incentives provided by the Kazakhstan government to families for education, many young people move to Kazakhstan for the education benefits. While many move with their families, others join extended family relations in Kazakhstan for the duration of their education. Many Mongolian Kazakhs also send children to work or to school in Ulaanbaatar, where there is a growing population of Kazakhs.

What benefits does the government of Kazakhstan provide?

Early Transition Years (1991-1996)

From 2006-2009, we worked to assess the migration situation of Mongolian Kazakhs. Essentially, three distinct periods of migration are identifiable and correspond with both macro-scale changes such as changes in economic conditions and immigration policies. During the first period (1991-1996), which was characterized by economic crisis in both Mongolia and Kazakhstan, the government of Kazakhstan passed a series of immigration reforms to assist ethnic Kazakhs in returning to Kazakhstan. In 1991 Kazakhstan passed the Resolution “On the Procedures and Conditions of the Relocation to Kazakh SSR for Persons of Kazakh Ethnicity from Other Republics and Abroad Willing to Work in Rural Areas.” In 1992, the quota system for Kazakhs repatriating to Kazakhstan was created through the 1992 Law on Immigration. The quota was intended to limit the number of migrants receiving benefits to a number that would not exceed government capacity. The annual quota is set for a specific number of “families,” not individuals. From the beginning, ethnic Kazakhs had the option of entering Kazakhstan either within or outside of the quota system.

The Kazakhstan government during the study period was not putting limits on the number of non-quota migrants who enter Kazakhstan, however, the quota levels themselves fluctuate annually. Oralman status, entitles migrants to basic types of assistance, such as medical, employment, language and education assistance at both the primary and secondary levels. Those within the quota qualify for additional assistance, including housing, transportation of family and goods from origin to destination and a lump sum allowance for each family member.

Mid-Transition Years (1997-2002)

Immigration to Kazakhstan for oralmandar continued to evolve during the middle transition years (1997-2002) with a new legal framework and changing annual quotas. In 1997, the Agency of Migration and Demography was developed as part of the 1997 Law on Migration and Population to assist migrants and to streamline citizenship procedures across different groups of oralman. Quotas overall were quite low during this period, reflecting changes in Kazakhstan’s economy and demographics. During this period, the quota declined from 3,000 families during the early transition period, to approximately 500 in 1999-2000, jumping again to 2,655 by 2002.

These changes in immigration policy and fluctuating quota numbers created a much more complex situation for Kazakhs living abroad who were considering migrating to Kazakhstan. Selectivity of migration increased during this period as well, reflecting both the increasing complexity as well as increased information flowing between Kazakhstan and Mongolia, leading to fewer new migrants during this period. Alex Diener, a Geographer at the University of Kansas, suggests that there were two primary reasons for these shifts: first, the invitations for diasporic communities to return led to greater return than anticipated by the Kazakhstan government leading them to impose more restrictive quotas to limit in-migration, and second, the in-migration of oralmandar declined as migrants realized the economic situation of Kazakhstan.

From the perspective of potential migrants, increased competition for inclusion in the quota represents an important shift in the perceived benefits and availability of quota benefits. Thus, changing economic circumstances in Kazakhstan and in Mongolia, combined with policy changes in Kazakhstan and changing perceptions of Mongolian Kazakhs about the benefits of moving to Kazakhstan begin to influence migration decisions during this period.

Late Transition Years (2002-2009)

During the late transition period, the most important change to immigration programs offered by the Kazakhstan government was the introduction of the “Blessed Migration” program on January 1, 2009. Like the other programs, this program continues to offer incentives to oralmander for immigration, however, this program targets particular settlement areas, specifically in the northern regions of Kazakhstan. In addition to providing subsidies and paid travel costs, the new program will provide low-interest loans to buy land or housing. This was perceived to be one of the most substantive challenges facing new migrants, especially in the current economic climate.

Acknowledgement of Organizations Funding the Research:

2008-2010

Barcus & Werner. National Science Foundation. “Collaborative Research: Networks, Gender, Culture and the Migration Decision-Making Process: A Case Study of the Kazakh Diaspora in Western Mongolia”.

Werner. Stipendiary Fellow, Glasscock Center for Humanities Research, Texas A&M,

2009-10; “Mobility, Immobility, and Transnational Migration among Mongolian Kazakhs” (International Studies Program fellow).

2009

Barcus & Brede. Collaborative Research: Networks, Gender, Culture and the Migration Decision-Making Process: A Case Study of the Kazakh Diaspora in Western Mongolia. Student-Faculty Summer Research Collaboration with Namara Brede, Macalester College. $4,615.

Werner & Emmelhainz, National Science Foundation Grant, 2009, Research Experience for Graduate Students (REG) Supplemental Grant to take graduate student Celia Emmelhainz to Mongolia.

Werner. International Research and Travel Grant, International Programs, Texas A&M, 2008; “Mobility, Immobility, and Transnational Migration among Mongolian Kazakhs”

Werner. Stipendiary Fellow, Glasscock Center for Humanities Research, Texas A&M, 2008-09; “Mobility, Immobility, and Transnational Migration among Mongolian Kazakhs” (Anthropology Department fellow)

2006

Barcus. Migration Decision-Making, Culture, and Trans-National Identities: A Case Study of the Mongolian Kazakh Diaspora. Association of American Geographers, AAG Research Grant. $1,000.

Barcus. Migration Decision-Making, Culture, and Trans-National Identities: A Case Study of the Mongolian Kazakh Diaspora. Macalester College. Wallace Travel and Research Grant. $5,950.

Werner. Women’s Interdisciplinary Seed Grant Research Award, Women’s Studies Program, Texas A&M, 2006; “Returning Home: Gender, Migration and the Kazakh Diaspora in Mongolia.”

Werner. Program to Enhance Scholarly and Creative Activities Award, Vice President for Research, Texas A&M, 2006; “Returning Home: Gender, Migration and the Kazakh Diaspora in Mongolia”

Werner. Faculty Research Enhancement Award, College of Liberal Arts, Texas A&M, 2005 “From an Imagined Homeland to Immediate Needs: Social Networks, Gender and the Migration of Kazakhs from Mongolia to Kazakhstan”

2004

Barcus, Fulbright-Hays Group Projects Abroad Grant, Contemporary Mongolia Program; awarded through the University of Pittsburgh; 2004, “Population, Environment, and Geo-Spatial Technologies in Mongolia”

Werner, Fulbright-Hays Group Projects Abroad Grant, Contemporary Mongolia Program; awarded through the University of Pittsburgh; 2004 “Women’s Experiences in Mongolia”

Researchers

Holly Barcus is a Professor of Geography at Macalester College. Her research focuses on the intersection of migration and rural community change with an explicit focus on how migration of ethnic minorities is changing the composition and character of rural places. She works in both the rural United States, specifically in Appalachia and the Great Plains, and in western rural Mongolia. One of the primary analytical and mapping tools that she uses in her research is a Geographic Information System; an invaluable tool for assessing spatial patterns and evaluating the underlying processes and factors that influence change at multiple scales. She received her M.A. from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and Ph.D. from Kansas State University, both in Geography. She currently serves as a board member for the American Center for Mongolian Studies, and on the editorial board of the Journal of Rural Studies (updated June 2018).

Dr. Cynthia Werner; www.cynthiawerner.com

Cynthia Werner is Professor of Anthropology at Texas A&M University. Her research focuses on the links between culture, gender, and the economy, with special focus on the region of Central Asia. Since the mid-1990s, she has conducted fieldwork in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Mongolia on topics that include transnational migration, international tourism development, bride abduction, the impacts of nuclear testing, gift exchange and bribery, and bazaar trade. She received her M.A. and Ph.D. in anthropology from Indiana University and has taught at the University of Iowa and Pitzer College. She is the Past-President of the Central Eurasian Studies Society (2012-15). She is currently the Department Head in the Department of Anthropology at Texas A&M University (updated June 2018).

Research Assistants

Celia Emmelhainz is the anthropology and qualitative research librarian at University of California, Berkeley. She worked as a research assistant on this project from May 2009-May 2010, studying issues of citizenship and the state in the migration of Mongolian Kazakhs. She received her MA in anthropology under Dr. Cynthia Werner in 2011, and her MLIS in library science in 2014. She now researches scholarly communications, research data management, and librarian professionalization in America and Kazakhstan (updated June 2018).

Namara Brede (BA Macalester College, 2010) spent two years working with Dr. Barcus as a research assistant for the Mongolian Kazakh Migration Project. During this time, he analyzed and processed geographic data associated with the project, and also traveled to Mongolia with the research team in May-June 2009. While there, he completed independent research on the changing socio-cultural landscape of Mongolian Kazakh Islam and Muslim identity, which formed the basis for his senior honors thesis. Namara is now working toward a master’s degree in geography at the University of British Columbia, where he plans to focus on spatial modeling of anthropogenic changes in grassland ecosystems.

Amangul Shugatai is a researcher at the Department of Regional Studies, Institute of International Affairs at the Mongolian Academy of Science. She graduated from the Nanhua University of Taiwan in 2010, with a Master of Arts degree in International Relations – Asia Pacific Studies 2010. Her undergraduate degree is Geographist and Geographical Teacher from Mongolia National University in 2004. She has worked as a researcher at the Social Economic Geography Department of the Institute of Geography-Geoecology of the Mongolian Academy of Science (MAS) from 2006 to 2016. Her job functions were related to the urban and rural field research, population settlement issues, migration processes and settlement and contemporary urbanization issues of Mongolia at the Institute of Geography-Geoecology. She studied issues of migration policy of Kazakhstan and worked as a research assistant with this project from June 2006 and June 2008- 2009. Currently her research is focused on Central Asia and Mongolia-Kazakhstan’s relations in Institute of International Affairs of the MAS. (updated July 2018).

Nurshash Shugatay is a teacher in Ulaanbaatar city from Mongolia. She graduated from Mongolian National University in Linguistics and completed a Masters Degree in Real Estate Land Economics. She worked as a research assistant with this project from May 2006 to July 2010. She also studied Linguistics in Russia to improve her language skills in 2008. She also studied Linguistics in Russia to improve her language skills in 2008 and attended an English Teacher’s Mentor Program as well as a conference titled “Improvement of Education in Remote Areas-For the Achievement of SDGs” in Tokyo, Japan (2018). (updated July 2018).

Publications and Presentations

Werner, C, Emmelhainz, C.*, H. Barcus. 2017. Privileged Exclusion in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan: Ethnic Return Migration, Citizenship, and the Politics of (Not) Belonging. Europe-Asia Studies: 69(10): 1557-1583. DOI: 10.1080/09668136.2017.1401042

Barcus, H.R. and C. Werner. 2016. Choosing to Stay: (Im)Mobility Decisions Amongst Mongolia’s Ethnic Kazakhs. Globalizations 14(2):32-50.

Werner, C. and H. R. Barcus. 2015. The unequal burdens of repatriation: A gendered view of the transnational migration of Mongolia’s Kazakh Population. American Anthropologist 117(2): 257-271.

Barcus, H.R. and Cynthia Werner. 2015. Immobility and the Re-Imaginings of Ethnic Identity among Mongolian Kazakhs in the 21st Century. Geoforum 56:119-128.

Brede, Namara*, Holly R. Barcus, Cynthia Werner. 2015. Negotiating Everyday Islam after Socialism: A Study of the Kazakhs of Bayan-Ulgii, Mongolia. The Changing World Religion Map: Sacred Places, Identities, Practices, and Politics. Ed. Stan Brunn. Springer Publishers: Netherlands. Pp. 1863-1890.

Barcus, H.R. and Werner, C.A. 2014. Transnational Migration, Local Economic Change, and the Persistence and Adaptation of Rural Livelihoods: A Case Study of the Kazakh Diaspora in Western Mongolia. The Sustainability of Rural Systems: Local and Global Challenges and Opportunities. Eds. Cawley, M. Bicalho, A.M.S.M., and Laurens, L. Galway National University Press, pp.143-151.

Werner, C., H. R. Barcus, N. Brede*. 2013. Discovering a sense of well-being through the revival of Islam: Profiles of Kazakh Imams in western Mongolia. Central Asian Survey 32(4):527-541.

Barcus, H.R. and Cynthia Werner. 2010. The Kazakhs of Western Mongolia: Transnational Migration from 1990-2008. Asian Ethnicity 11(2):209-228.

Werner, Cynthia and Holly R. Barcus. 2009. Mobility and Immobility in a Transnational Context: Changing Views of Migration Among the Kazakh Diaspora in Mongolia. Migration Letters 6(1):49-62.

Barcus, Holly R. and Cynthia Werner. 2007. Transnational Identities: Mongolian Kazakhs in the 21st Century. Geographische Rundschau: International Edition 3:4-10.

Presentations at Professional Conferences

Barcus, Holly. 2013. “Place identity and immobility choices among ethnic minorities: Transitioning landscapes in a transnational community” 21st Colloquium of the Consortium for Sustainable Rural Systems, International Geographical Union. Nagoya, Japan August 2013.

Barcus, Holly. 2013. “Place Identity and Immobility Choices among Ethnic Minorities: Transitioning Landscapes in a Transnational Community”, Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers, Los Angeles, CA, April 2013.

Barcus, Holly. 2012. “Kazakhstan is my homeland; Mongolia is my fatherland”: Considering the role of place identity and other cultural factors in shaping mobility and immobility decisions in a transnational community” Race, Ethnicity and Place Conference, Puerto Rico, October 2012.

Barcus, Holly. 2012. “Kazakhstan is my homeland; Mongolia is my fatherland”: Considering the role of place identity and other cultural factors in shaping mobility and immobility decisions in a transnational community” Central Eurasian Studies Society Meeting. Tbilisi, Georgia. July 2012.

Barcus, Holly. 2011. Transnational Migration, Globalization, and Local Economic Change in Western Mongolia: An Examination of New Rural Development Challenges in the 21st Century. 19th Meeting of the International Geographical Union Commission on Rural Sustainability, Galway, Ireland. August 1-7.

Barcus, Holly. 2011. Transnational Identities, Migration, and the Importance of Cultural and Social Ties between Communities: A Case Study of the Mongolian Kazakh Diaspora. Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers, Seattle, Washington, April 2011.

Barcus, Holly. 2009. Transnational Migration, Local Economic Change and the Persistence and Adaptation of Rural Livelihoods: A Case Study of the Kazakh Diaspora in Western Mongolia. 17th Annual Colloquium of the International Geographical Union Commission on the Sustainability of Rural Systems, 2009. Maribor, Slovenia.

Barcus, Holly. 2009. Keynote Lecture for Internationalism Week. “Modern Nomads: Transnational Migration and the Kazakh Diaspora of Western Mongolia. Minnesota State University. 20 November 2009.

Barcus, Holly. 2008. Mobility and Immobility in a Transnational Context: Changing Views of Migration Among the Kazakh Diaspora in Mongolia. 105th Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers. Las Vegas, Nevada.

Barcus, Holly & Werner, Cynthia. 2008. The Kazakhs of Western Mongolia: Transnational Migration from 1990-2008. Invited conference. Contemporary Mongolia: Transitions, Development and Social Transformations. 14-17 November 2008. University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Barcus Holly. 2007. Migration decision-making, culture, and trans-national identities: A case study of the Mongolian Kazakh diaspora. Association of American Geographers, 103rd Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA. April 2007.

Cynthia Werner, Mobility, Immobility and Return Migration: The Impact of Transnational Migration on the Kazakh Diaspora in Mongolia. American Anthropological Association 107th Annual Meeting. San Francisco, California. November 19-23, 2008

Other Invited Presentations and Outreach:

2010

Barcus, H. Invited Lecture. “Nomads and Transnational Migration: Reflections on Fieldwork and Community Change in Western Mongolia. Conversations About Our Scholarly Lives (CASL) sponsored by the Center for Scholarship and Teaching, 3 May 2010.

Barcus, H. Invited Lecture. “Modern Nomads: Transnational Migration and the Kazakh Diaspora of Western Mongolia. University of Minnesota, 26 March 2010.

Barcus, H. Guest lecture. “Implications of Transnational Migration for Mongolian Kazakhs.” Human Geography of Global Issues, GEOG111, March, 2009.

Barcus, H. Guest lecture. “Implications of Transnational Migration for Mongolian Kazakhs.” Human Geography of Global Issues, GEOG111, February, 2009.

Werner, Cynthia. Returning Home: Gender, Migration and the Kazakh Diaspora in Mongolia. Women’s Studies Brown Bag Lecture. March 6, 2009.

Werner, Cynthia. Invited Lecture. “Field Research Among the Kazakhs of Mongolia.” Kazakhstan State University. Almaty, Kazakhstan. 6 May 2010.

Werner, Cynthia and Celia Emmelhainz. Poster Presentation. “Moving Towards the State: The Benefits of Economic Citizenship for Mongolia’s Kazakhs.” Society for Economic Anthropology Annual Meetings. Tampa, Florida. 8-10 April 2010.

Werner, Cynthia. Invited Lecture. “Ethnographic Research Among the Kazakhs of Mongolia.” Texas A&M Anthropological Society. 9 March 2010.

Werner, Cynthia and Holly Barcus. Keynote Lecture for Museum Exhibit Opening. “Modern Nomads: The Kazakhs of Mongolia in the Contemporary World.” Brazos County Museum of Natural History. Bryan, Texas. 18 February 2010.

2009

Barcus, H. Invited Lecture: “Why do all the Yurts have Satellite Dishes? Globalization and Local Livelihood Change in Western Mongolia. Minnesota State University. 20 November 2009.

Barcus, H. Guest lecture. Implications of Transnational Migration for Mongolian Kazakhs. Human Geography of Global Issues, GEOG111, February, 2009.

2008

Barcus, H. Transnational Kazakh Migration in Western Mongolia. GEOFEST Minnesota. 25 October 2008. Macalester College Geography Department.

Barcus, H. Invited Guest Lecture. Land without Fences? A Look at Contemporary Mongolia. Teaching about the Geography and Cultures of Asia is the Middle Grades, a development workshop for teachers, sponsored by the Minnesota Humanities Center. February.

2006

Barcus, H. Invited Guest Lecture. Migration Decision-Making, Culture, and Transnational Identities: A Case Study of the Mongolian Kazakh Diaspora. Minnesota State University, Geography Department Colloquium. December.