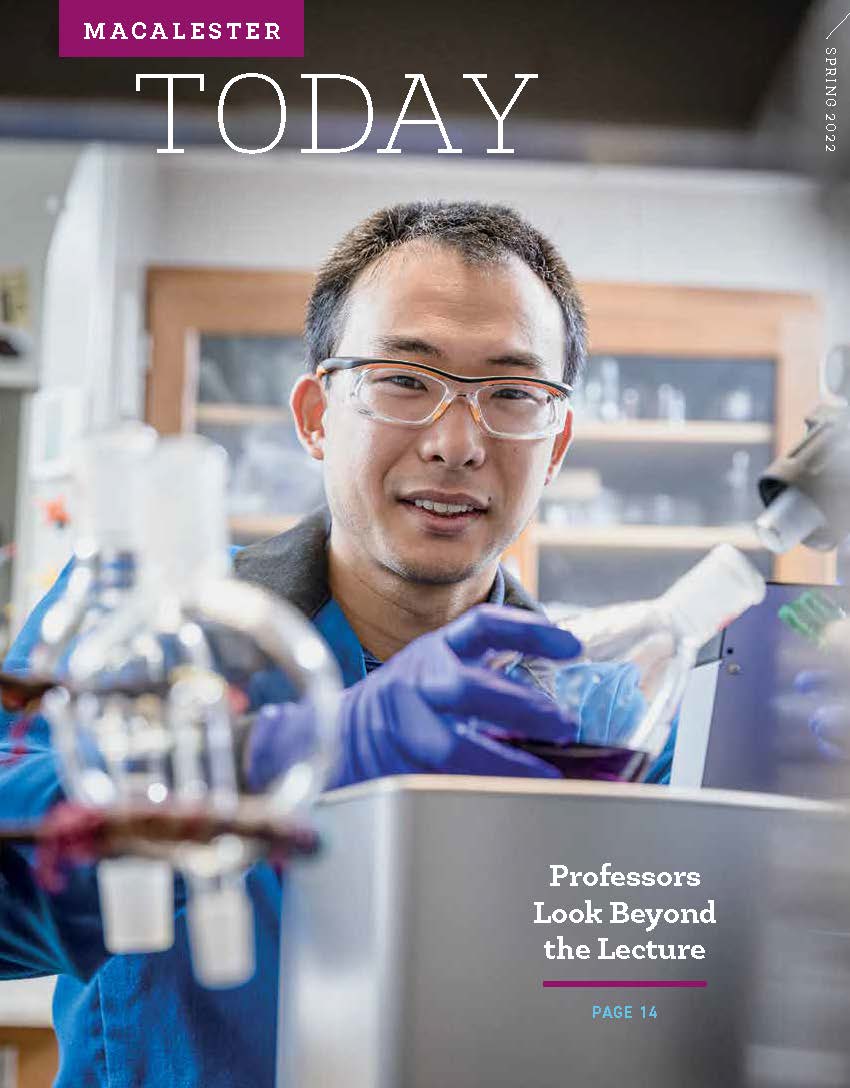

By Erin Peterson / Photos by David J. Turner

Kelsey Grinde knows how important it is to think broadly and creatively about teaching.

It wasn’t just that the assistant professor of mathematics, statistics, and computer science had trained to be a high school mathematics teacher, and that she’d learned plenty of techniques to help students find their footing. It was also that she herself had benefited from teaching that went beyond lectures and included plenty of personalized attention. “I was fairly shy in class as a college student, and sometimes I was one of the only women in the room,” she says. “The kinds of active learning techniques that I use now are the ones that really worked for me as a student. They helped me get a lot further in math and statistics than I ever thought I would have.”

Grinde isn’t alone. Creative teaching can crack open even the toughest subjects. It can spark a student’s passion and fuel work for a lifetime.

And at Macalester, this kind of effort and experimentation around teaching is commonplace, says Joan Ostrove, director of the Jan Serie Center for Scholarship and Teaching. “Faculty are drawn to Macalester because they want to be outstanding teachers,” she says. “They want to be part of a community that thinks about teaching and values it.” To support that effort, the center offers regular programming and resources related to pedagogy and advising.

To learn more about the imaginative work happening inside the classroom (and sometimes, beyond it), we asked a few faculty members to share the foundational ideas and creative approaches that propel their teaching.

Flip the classroom

Assistant professor of mathematics, statistics, and computer science Kelsey Grinde had been using a traditional lecture format in the first statistics classes she taught before arriving at Macalester in 2019. But when the pandemic hit partway through her first year at Macalester and classes moved to Zoom, she realized that she needed to rethink her approach. “I didn’t really want to be on Zoom talking at students for a long time, for everybody’s sanity,” she says.

So she teamed up with department colleagues Brianna Heggeseth and Leslie Myint to create a series of five- to fifteen-minute videos that teach concepts like linear regression models, or show how to interpret data sets linked to smoking and lung function. Students watch them in their own time, study the text, then ask questions and work through problems during class. This approach, known as a flipped classroom, offers Grinde a chance to more clearly understand when students have mastered an idea and when they need a bit more help.

Now that students are back in person, she’s kept this flipped classroom in place. Students watch the videos on their own, then work in groups to solve problems in class. Grinde walks around the room, dropping in on groups to check on their progress. Oftentimes, she uses a Google doc to monitor how the class is doing overall with group discussion prompts.

The new approach has added significantly to Grinde’s workload. Creating the videos is extraordinarily labor intensive—she and her collaborators spent most of their summer working on the videos, rather than other research and projects. But she’s also been particularly happy with the way that it has transformed the classroom. She loves it when she can see students talking animatedly with each other about concepts or helping one another with specific knotty problems.

She knows that being able to watch videos again and again can be helpful for students who simply need a little more time and repetition to cement their learning.

Grinde is also delighted to have more time to get to know her students on a personal level. During class, “I’m not an authority figure standing up at the front, I’m sitting down next to them and helping them work on something,” she says. “This allows me to have conversations with students who—if they just came to class and didn’t come to my office hours—I might otherwise never have really met.”

She’s hopeful that the approach will open up statistics to more people who might otherwise have stopped after a single course. “For many people, there’s a lot of internal dialogue about how they’re terrible at math, or they’re not good with computers. But I hope that this is one way to get more people to realize how cool statistics is—and that they can do it,” she says.

Embrace the forgetting of learning

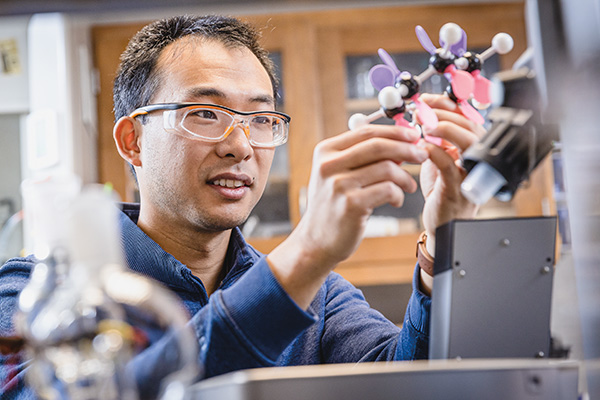

Associate professor of chemistry Dennis Cao teaches what is often considered one of the toughest courses at Mac: organic chemistry. The class, essential for pre-med hopefuls, includes lessons on molecular geometry and electron flow that can scramble the brains of otherwise accomplished students.

Cao has one message he wants all of his students to hear before they give up: The work is supposed to be difficult. “I tell students all the time that yes, I’m throwing them into the deep end—and that’s how it should feel. I don’t want to go shallow,” he says.

That might seem like cold comfort, since Cao himself long ago mastered the material. But as a novice in other areas of his life, he intentionally throws himself into the deep end all the time, too, trying a new hobby every six months. He’s picked up woodworking, fishing, and even 3D printing—cheerfully acknowledging that he’s not an expert in any of them, despite his efforts. He knows, viscerally, the feeling of being overwhelmed by a new subject.

“I think languages are a fun thing to learn, but I used to get so annoyed when I couldn’t even remember three words—what’s the point?” he says. “But that is the point. You can’t remember three words, so you have to just keep doing it, and doing it, and doing it.”

Instead of getting frustrated about the time and repetitions required to understand a concept and establish it firmly into long-term memory, students can instead acknowledge it, plan for it, and embrace it. Learn, forget. Learn it a new way, forget again. Eventually, students do remember. And when they do, they don’t just remember the information for a test, they understand it.

When students internalize this approach to learning difficult subjects, it pays dividends: Cao reminds pre-med students in his class that this is the warmup: In medical school, they may be taking five classes that are all as tough as organic chemistry in different ways, and once they know what it takes to succeed in a very difficult class, they will be ready for the new challenges of medical school.

Cao says that students who learn to embrace the challenges of organic chemistry often find that the approach benefits them broadly. “Most of my students don’t go on to be organic chemists, but I have had students come back and tell me that doing the work in my class helped them in another totally unrelated class,” he says. “I find a lot of gratification in knowing that, in the long term, this approach helped.”

Get outside the classroom

By the time that students enter assistant professor of sociology Erika Busse’s upper-level course, “Qualitative Methods,” they’ve spent plenty of time learning from research that uses qualitative research methods such as observations and interviews. In Busse’s classroom, they finally have the chance to employ those qualitative methods in their own original research.

By the time that students enter assistant professor of sociology Erika Busse’s upper-level course, “Qualitative Methods,” they’ve spent plenty of time learning from research that uses qualitative research methods such as observations and interviews. In Busse’s classroom, they finally have the chance to employ those qualitative methods in their own original research.

Busse has her students design a project to understand an aspect of race and ethnicity more deeply by choosing a single intersection near campus and studying social dynamics in it over the course of a semester. Students have chosen to study everything from ways to create community to the ways advertising differs for drivers, pedestrians, and public transit users.

Busse says that preparing to do ethnographic research can provoke anxiety in students who are used to burrowing into books and acing tests. Instead, they have to adjust to a more fluid and uncertain process of observation, interviews, and study: “They want to know: What am I going to say? What should I do? Should I take out a notebook or take notes on my cell phone?” she says. “They’re used to being challenged intellectually in the classroom or with their friends, but they’ve never gone out themselves to observe and collect data. That can be disorienting.”

Busse encourages students to be open to the messiness of the process, and she has them regroup in class to share their experiences, troubleshoot, and even provide advice to others. One of her great joys is seeing the growth that they experience as they move from idea to research to finished paper.

And although not all students end up loving the process, they do gain a greater appreciation for the challenges of research that aren’t fully visible in a published journal article. “If you want to actually learn social dynamics, you have to be open to the idea that you won’t always have control. You’ll always depend on other people,” she says. “Learning that? It’s priceless.”

Create standout social media posts to highlight important academic ideas

See students’ Instagram projects at @mac_psyc394.

In the summer of 2020, assistant professor of psychology Morgan Jerald was contemplating changes to her upper-level seminar, “The Psychology of Black Women,” against the backdrop of the uncertainty of the pandemic and the grief and rage erupting in the Twin Cities over the murder of George Floyd.

That summer, she’d begun noticing a trend dubbed “Power Point activism”—slideshows on Instagram that paired distilled insights with compelling graphics to make a persuasive point. She realized that they could also be a launching point for her students who wanted to bridge the divide between academic research and wider impact, so she developed a short, powerful Instagram project.

She asked each student to write an op-ed about any issue related to the psychology of Black women. Then, students created an Instagram slideshow, complete with images, based on the content of the op-ed.

Even students well-versed in the social media platform’s nuances found the project one part thrilling, one part hair-raising. It’s anything but easy to convey complicated concepts in an engaging and visual way. “Having to distill something into a really short format is sometimes even harder than having no word limit at all,” Jerald says. “It requires you to communicate really clearly.”

Students created slideshows on topics ranging from health care disparities to segregated neighborhoods to education. They carefully sequenced the slideshows to start strong, build arguments, and provide resources for viewers to learn more. Jerald says that the projects gave students essential practice in communicating effectively to non-academic audiences about important issues.

The work has already earned significant external praise. Last year, the project received an Action Teaching Award from the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, a group of three thousand scientists who seek to apply theory and practice to today’s critical problems.

Jerald says she wanted the project to remind students that they can have a voice in issues that are important to them. “I hope that my classroom and assignments can be used as a space for students to process what’s happening and feel more empowered to act on it,” she says.

Channel passion to create art

Wallace Professor of Art Ruthann Godollei knows that Mac students are driven and passionate about a variety of issues. In her “Dissent” course, she requires students to channel that energy into creating meaningful art that goes beyond the craftsmanship in order to say something larger about a social or political cause.

In the course, she teaches students about art linked to dissent and protest throughout history and around the world. Then, she has students create their own works based on the ideas that are important to them. Over the years, students have made stickers about immigration, linocuts to propel fundraising efforts, and specialty cards for Bike to Work week. “I want them to do their ideas, not my ideas,” she says.

Art offers a particularly kinesthetic learning experience, says Godollei: “So many of us are stuck in virtual realities. Art helps people get back into their bodies, back into the material of their hands.” It’s also a way for students to find another way to take action on something they care about.

Godollei says that when students transform their ideas into tangible artwork, they see their own abilities, and the world they inhabit, in a new way. “It’s a wonderful feeling when you’ve got a whole classroom of students getting their hands inky, exclaiming with each other over what they’re making,” she says.

And regardless of what they pursue in their lives later, they have a deep understanding of the challenges of creating art designed for impact. “It also helps them appreciate the labor of art, the human intelligence behind it, and the real struggles that people have gone through.”

Erin Peterson is a Minneapolis-based writer.

April 21 2022

Back to top