Sophie Hilker ’20

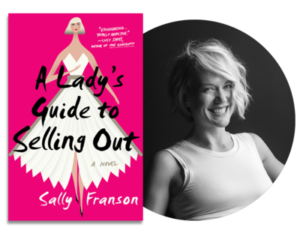

Visiting Assistant Professor Sally Franson’s debut novel A Lady’s Guide to Selling Out is a finalist for a Minnesota Book Award in the category for Novel & Short Story. A Lady’s Guide follows Casey Pendergast, English major turned ad-agency brand strategist, as she attempts to recruit well-renowned authors to represent corporations as brand ambassadors in order to creatively reinvent their reputations under the orders of her hard-to-please boss. Though initially enthusiastic about the assignment, everything changes when Casey falls for one of her writers and begins to question the cost of her own conscience. Described by Franson as a “bildungswoman,” a female take on bildungsroman, the novel has received praise from the likes of Amy Bloom, The Star Tribune, and has been heralded as the next The Devil Wears Prada.

The Words sat down with Professor Sally Franson to discuss A Lady’s Guide, The Minnesota Book Awards, and all things literature and ethics. This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

How does it feel to have your first novel be nominated for the prestigious Minnesota Book Award?

Oh, it’s so fun! I was very surprised. I didn’t know about it and then my friend Steph texted me, “Congratulations!” And I texted back, “For what?” And then she went into the shower and I had to Google myself to figure out what was going on. So much of being an artist is that a lot of things pass you by, and so then when things do come along, I feel so grateful because I don’t take it for granted at all. It’s so meaningful to be recognized and see someone recognize the work that went into it. Because it is a labor of love–to write a book–to make anything really.

Did you always know this would be your first novel? Has this been a story that you’ve been carrying along with you for a while and wanted to put down into words?

No. I got my MFA at [the University of] Minnesota and was writing my MFA book which was my hybrid, experimental, nonlinear tome, which I never finished. And this started probably a year after I finished graduate school really as a joke, just trying to make my friends laugh. I wrote it in big font in Google Docs–I didn’t care. And it took me a long time to think, “Oh, maybe this could be more than just my goof-around thing.” It was such a great place to start from ‘cause it was so low stakes for me, and it was so fun for me. I spent so many years striving, I’d forgotten that it’s okay for writing to be fun, and it’s okay for it to delight.

From where did you draw inspiration for your novel?

I was dating a guy who worked in advertising and I had never met anyone who worked in advertising. And I thought, “You’re so smart. You’re so funny. You’re so creative. And you’re using all that to make KFC commercials.” It just never occured to me that you could have all those gifts and then use it like that. And I thought, “Man, if I had been 25, and some company would have said ‘Come here, I have a job for you,’ I would have done it in a second!” I was making like $7,000 a year. So I started to wonder what it would be like to work somewhere like that. It’s partly because of that and partly because I saw writer friends of mine in their jobs getting put on these crazy quote systems for social media. A writer friend of mine said very candidly, “I feel like I’m being put on an assembly line.” So I wondered, what’s the end of the road for that? What’s the end of the road if we not only completely commoditize ourselves as artists but commoditize ourselves as people? If people are brands, what’s the end result of that? I was really preoccupied with that for a long time. It’s not my obsession anymore, but it was my obsession for a few years. And now I just post Instagram pictures of my dog and not think about it very much.

That’s valid, too. Sometimes you’ve just gotta cope like that.

Yeah, totally! I mean, that’s the fun part of writing a book, there’s no answers to these problems; we’re living the questions.

It sounds like there were a lot of ethical thoughts and questions that went into this process. Have you been preoccupied with the ethics behind the writing and publishing process as well?

Oh, yeah. It threw me off a lot to think that you write something out of love, and you want to share it, and then dollar amounts start getting assigned. That’s disorienting because, if you allow it to, it starts putting you in competition with other products, which I think is a really dangerous way to think about the arts. I go back to thinking that this is a gift I’m giving away, but I also need to be able to pay my heating bills, and buy my groceries, and pay back my student loans. We live in a commodity culture, so is there a way I can live through that while still keeping my integrity? And I don’t mean my artistic integrity. I don’t have highbrow notions of what it means to make money off of a book, but I do have notions for what feels good for me and what doesn’t feel good for me.

So if we’re thinking of books in competition, not only as products, but within the context of the Minnesota Book Awards as well, one of the judging criteria is literary merit. How would you define the worth of a book? How do you even begin to define that?

So there’s got to be some difference between literary merit and consumer merit. I think there are people writing books for entertainment purposes and there’s a place for that. When I was really sick in my mid-twenties, all I read were vampire mysteries. And I’m sure those were really hard to write because all books are hard to write, but I don’t think the author was writing them to give us a greater sense of what it means to be human. And maybe that’s what I would consider literary worth: something that is asking us to think about what it means to be human. Worth, to me, is when I read something and I know that my internal landscape has been changed as a result of that.

Another part of the judging criteria, which I think you engaged with a little bit in your previous answer, is how effective a novel is in engaging it’s target audience. Who do you feel was your target audience for A Lady’s Guide?

I think you learn your audience as you go through the publishing process. Because when my agent first asked me, “Who are you writing this for?” I said, “I’m writing this for everybody! It’s for everyone!” And that’s naiveté at work because I never thought that I was only writing it for women, but probably by making women all the main characters, and having them have complex relationships with each other, shunts [the book] off into a certain category. If you’re writing a workplace novel about men, that can be for everybody. But a workplace novel about women is “women’s fiction.” So I think my target audience was really women who are my age, college educated and beyond, who were having serious questions about how to make meaning in a culture where the types of meaning being offered seem fairly empty. When I’ve heard back from readers, that’s always what they’re engaging with. And I grew up in suburban Wisconsin, and a lot of my friends are married with kids and don’t have time to read a lot, so it was really important for me that people like my friends from home could read the book and not feel like there was gatekeeping at play with certain performed, urbane sophistication. I think it’s my Midwestern-ness that makes me chafe at all levels of pretense. That kind of accessibility has always been really important to me.

What’s one of the weirdest things you’ve ever done to get into “the zone” for writing?

Two things. One, I would take a tennis ball and I would take walks and I would bounce the tennis ball because it would require a lot of motor functioning in my body, but my brain could wander. My friend Dennis was sitting at Victor’s 1959 Cafe, and he messaged me, “Sally, are you okay? Because I saw you wearing a trench coat and headphones, bouncing a tennis ball down the sidewalk and you looked really mad.” My serious face is also my mad face, but I was so deep in the process that it had never occurred to me that I looked strange. Exercise is really good for writing, like yoga, and breathing exercises. The other thing is I have a harmonium in my office, so sometimes I’ll play music.

Not in this [Macalester English Department] office, I’m assuming.

Haha! No! I think I’d get numerous complaints.

Your book has often been compared to Mad Men, The Devil Wears Prada, and Jane Austen’s Emma. How do you feel about these comparisons, and do they accurately reflect the overall content or theme of the book?

I’ll try my best [to answer], but just know that I am an unreliable narrator. Emma, I’m very flattered by. I think Jane Austen is a genius and the sense of irony that she uses I hope readers get from my book. [Casey] is a first person narrator and you can take what [she’s] saying with several cups of salt. Mad Men I think was a comparison because the book also takes place in the advertising world. I really admire the world of that show, but I do not admire its stance towards the characters of the show, which I feel is pretty critical. I prefer a kinder stance towards my characters, even the ones who are terrible people. The Devil Wears Prada… I don’t know where that came from! Maybe because Casey has a difficult boss, so everyone was like “Oh, The Devil Wears Prada!” That was the one that surprised me the most, but I realized that I am open to people making all sorts of comparisons if it means they’re going to the library or the bookstore. They can call it whatever they want, just don’t call it late for dinner.

Did you have to edit out anything in the process of publication that you wish had been in the final product of the book?

There were some bad jokes in there that I really wish had stayed in. I probably won’t get in trouble for this – haha! I don’t want to give anything away, but at one point Casey ends up working at a bookstore. Originally, she was working at a Barnes & Noble and I had a chapter called Barnes & Ignoble because she was in a period of crisis. And I just thought that was the cleverest thing, but they [the publisher] got rid of it because they have relationships with Barnes & Noble–it’s selling the book! So I had to make up a bookstore, which actually ended up being kind of fun because I called it–because I was a sasspot–“Wendys’s.” So not Wendy’s like the fast food chain, but W-E-N-D-Y-S-’-S because it was run by two women named Wendy.

Do you have any advice for aspiring young writers?

I feel honored and also inadequate giving advice, because who am I? And I feel like real writers will ignore anything that I say because that’s what I always did. But the advice that I try to take now is to just listen to how people talk. I really like writing dialogue, so I try to listen to how people talk and hang out with people who talk differently from me. So I’m a writer. I hang out with other writers. We’re all hyper-articulate people who verbalize a lot of our inner landscape. There are many people in this world who have at least as colorful of an inner landscape who are not articulating things in as precise a way, as exhaustive a way, and I think that’s worth thinking about so we’re not just writing books for the kind of people we are, but we’re writing books for a broader literary and reading culture. We’re human beings; we experience so many of the same things in this world. Being able to recognize that in another person, even though it’s coming out in a way we wouldn’t have said or necessarily articulated, I think, is really important work not only as a writer, but as a person.

Have you started on any new novel ideas yet?

Yeah, I’m working on one right now, which is about a group of five friends in a period of five years, from 2011 to 2016, who are in their thirties. And it takes place mostly at weddings.

Very cool. Women protagonists?

Women protagonists. It’s not that I don’t want to write men, it’s that… Well, I guess it is that I don’t want to write men because if I did, I’d probably do it. There are male characters in A Lady’s Guide, but I just like putting women front and center. The fact that it’s still so radical means that I just have to keep doing it until it’s boring.

The Words extends a huge thank you and congratulations to Professor Sally Franson! Catch Sally on Friday, March 15th, at a “Meet the Finalists” for the Minnesota Book Awards event at the University of Minnesota Elmer L. Andersen Library at 7:00 PM. Authors from each category will take part in a panel discussion about their work. This event is free and open to the public. The winners of the Minnesota Book Awards will be announced on Saturday April 6, with the ceremony beginning at 8:00 PM. Tickets start at $40. For more information, visit the Minnesota Book Awards’ website. A Lady’s Guide to Selling Out is available wherever books are sold.