MN Environmental Issues

Contact

Community Engagement CenterMarkim Hall, Third Floor 651-696-6040

cec@macalester.edu

facebook twitter instagram

From Line 3 to PolyMet to the Upper Harbor Terminal and beyond, Minnesota is experiencing a confluence of increasingly urgent and fluid developments that threaten the natural environment and Indigenous lands. The opportunities to engage cross urban and rural regions — both in-person and remotely — and require a multidisciplinary, multifaceted approach.

It is part of the Community Engagement Center’s mission to help the Macalester community understand the context for engagement, particularly for issues that affect a large number of students, faculty, and staff. This page includes contextual information and overviews by topic, a variety of ways to get engaged, and more. Please note that participants of in-person engagement will be expected to follow the Mac Stays Safer Covid-19 safety protocols.

Line 3

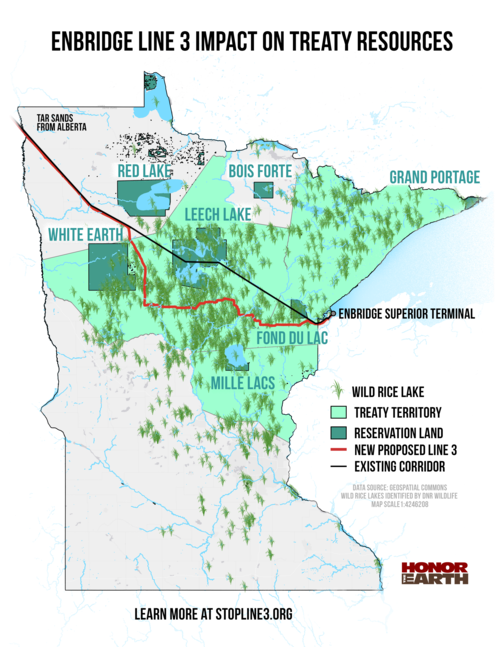

Line 3 is a tar sands oil pipeline that runs from Alberta, Canada, to Superior, Wisconsin. The pipeline was built in 1968 by Enbridge, an energy transportation company headquartered in Calgary, Canada. The original Line 3 has developed cracks and holes, and currently carries half the capacity of its original oil volume. Enbridge would like to replace the pipeline and restore its original capacity. If completed, the pipeline would move 800,000 barrels of oil per day across 200 bodies of water and 75 miles of wetland in Minnesota, much of it located near Ojibwe territory.

Supporters of the Line 3 replacement cite rural job creation, property tax revenue, and the need to stabilize the oil industry as key reasons to build the new pipeline. Its opponents argue that Minnesota would accelerate climate change, jeopardize watersheds, violate Ojibwe treaty rights, and increase drug and sex trafficking in an around Native American reservations.

Enbridge’s proposal was swiftly approved and constructed in all states and provinces along the route except Minnesota. Here, environmental activists and Indigenous groups demanded a more stringent and democratic regulatory process. In spite of their efforts, the project was fully permitted by state regulators in November of 2020 after five years of review.

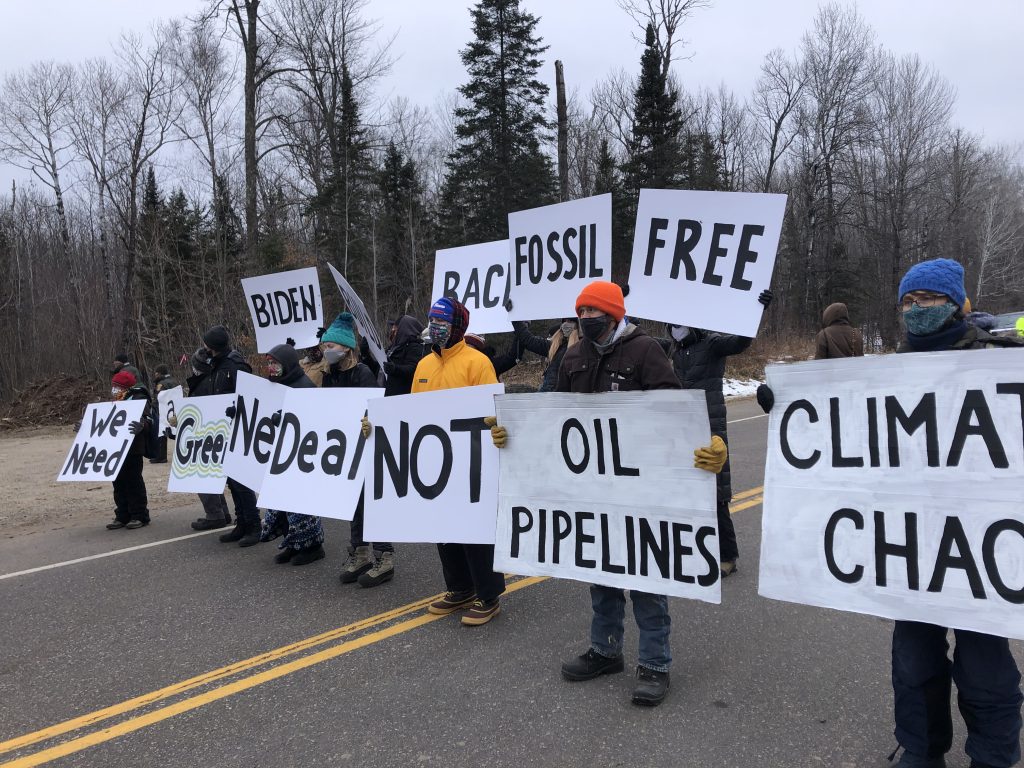

Presently, Indigenous groups and their allies have been mounting direct action resistance along the pipeline route, and pressuring Gov. Tim Walz to place a stay on construction until all the legal appeals are considered. The U.S. president has the power to reject the pipeline, but Joe Biden has not announced a specific initiative affecting Line 3 thus far.

Copper-Nickel Mining in Minnesota

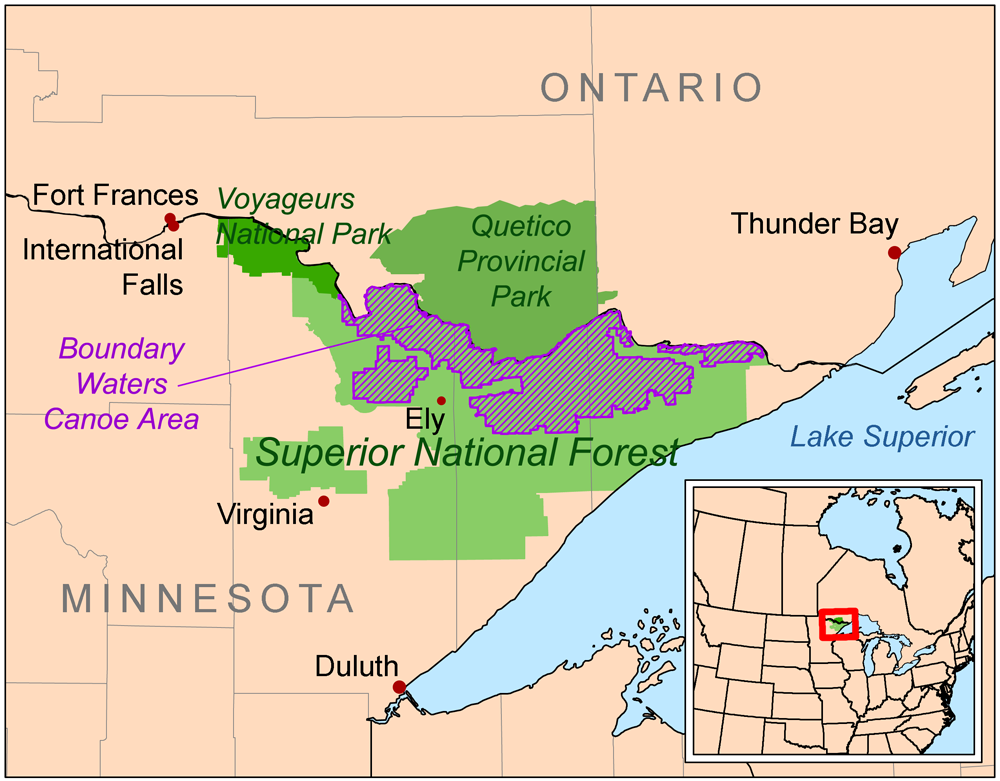

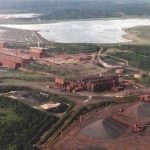

Two multinational companies are bidding to begin mining copper, nickel, and a number of other precious metals. The first company, Twin Metals, hopes to build an underground copper sulfide mine in a publicly-owned buffer strip adjacent to the federally protected Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW), well within the wilderness’ watershed near Ely, MN. The second company, PolyMet, would renovate an old mining facility and dig an open-pit mine on mostly private land. Both companies would be mining using a technique known as sulfide ore mining, and the mines would be slated to be in operation for 20-25 years.

The mines would be located in a region of the state known as the Iron Range. Until the 1970s, iron-ore was the economic backbone of this region, in fact many of the towns were founded as mining communities. Since changes in supply chain abruptly reduced the demand for Minnesota ore, the Iron Range has been struggling economically. Service industries (i.e. healthcare, education, etc.) have replaced mining as the primary industry in the region, but increasing demands for services can be seen as a byproduct of growing natural amenity tourism and natural amenity-induced immigration.

Supporters of the mine would like a new mining boom to bring new residents to the area and give local residents well paying, year-round, dignified work that honors the region’s mining heritage. The companies would pay property taxes that could support withering Iron Range towns. Many supporters feel that residents of the region itself should decide its economic development strategies and are frustrated by the pattern of city-dwellers dictating their best interests. While many residents in the area do have a family history of the prosperity that active mines once brought, there are also many drawn to the natural beauty and resources who have a livelihood based on its preservation. Furthermore, renewable technologies such as solar panels require metals that would be mined here. As they are necessary for a green transition, proponents argue it is better to mine them in a place like Minnesota that has high environmental regulatory standards. The companies acknowledge that this type of mining has caused severe water contamination in the past, but contend that new technologies would prevent such disasters.

Mine opponents counter that short term economic gain of copper nickel mining in the Iron Range is far outweighed by the long term loss of natural resources and loss of revenue from natural amenity tourism. A second mining boom would mean a return to a boom-and-bust economy reliant on fluctuating mineral prices. They also point out that there is not one copper-nickel mine in existence that hasn’t leached acid into the surrounding areas. Twin Metals could pollute the Rainy River watershed, which includes the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW), and PolyMet could pollute the Saint Louis Watershed, which flows to Lake Superior. Ojibwe bands in the region hold that the mines would violate their federally recognized right to hunt, fish and gather in ceded and unceded treaty land. Acid mine drainage poses a threat to wild rice, a crop of spiritual, nutritional and economic importance to the Ojibwe. Though the companies have pledged to clean up, opponents say they have reason to doubt that they will stick to their word given the track record of mining companies going bankrupt before they follow through.

Both mines are owned by large multinational mining companies. Polymet is owned by Switzerland-based mining giant Gencore. Polymet traded forest land in 2018 with the U.S. Forest Service so they now are located on private land and own the mineral rights. Twin Metals is owned by Antofagasta, a major mining company in Chile controlled by one of Chile’s wealthiest families (the Luksic Family) with controversial ties to the Trump family. Twin Metals leases include 5,000 acres of federal public land in Superior National Forest with the proposed mine operating on 100 acres of company owned land. The federal government currently still owns the mineral rights.

Just like Enbridge, the mining companies have faced a regulatory path much longer and more expensive than anticipated. PolyMet submitted its first Environmental Impact Statement in 2010, and has since gained and lost permits. After initial setbacks from the Obama Administration, Twin Metals is working on its first EIS (Environmental Impact Statement), while the Minnesota legislature debates a bill that would permanently ban mining in the federal land surrounding the BWCA. The future of both mine proposals is uncertain.

Upper Harbor Terminal

The Upper Harbor Terminal (UHT) is a 48-acre parcel of land located on the Mississippi River in North Minneapolis. Since 2015, the City of Minneapolis has been planning to redevelop the UHT in partnership with United Properties and First Avenue.

The plan has been billed by Mayor Jacob Frey and others as an equity project. For decades, industrial polluters have cut off North Minneapolis residents from access to the Mississippi River. They say that the project will benefit the economy of North Minneapolis and will center residents in every stage of development.

Many community members don’t share the Mayor’s vision. An opinion piece by Friends of the Mississippi called the project “public funding for white-owned business wrapped in the holy cloth of equitable development.” The plan has been heavily criticized for its exclusionary planning process, lack of environmental review, and potential to displace residents. Its opponents believe it would create wealth for white-owned businesses and entrench existing wealth disparities. There is also concern that it could draw police: urban redevelopment projects have been shown to intensify misdemeanor policing and non-emergency 911 calls.

To address these concerns, activists formed the Northside Eco-Harbor Co-Creation team and pressured the City Council to hear their concerns. As a result of their work, the final coordinated plan draft currently open for public comment holds the original proposal in place, but includes the possibility of community ownership models such as a community benefits agreement or a land trust. With more cooperative options now in the picture and the grant deadline nearing, community groups continue to push for a plan that is environmentally sound and will meaningfully benefit North Minneapolis.

Helpful Articles

Line 3

Lawsuit seeks to halt Line 3 pipeline, alleging faulty approval process

The Fight to Stop Line 3 is an up-to-date blog about Line 3 resistance maintained by StopLine3.org

Timeline (2013-2018) of Line 3 in Minnesota

Man Camp Fact Sheet from Honor the Earth

Healing Stories MN is a blog by Scott Russel of the Sierra Club with digestible writing on Line 3 developments

Copper-Nickel Mining

Bill to Ban Copper nickel Mining Draws Sharp Contrast Between Boundary Waters Iron Range from NPR, Feb. 6, 2020

In Northern Minnesota, Two Economies Square Off: Mining vs. Wilderness is a feature helpful to understanding the cultural context by The New York Times, Oct. 12, 2017

Upper Harbor Terminal

The Upper Harbor Terminal amended concept plan (PDF)

Friend’s of the Mississippi UHT Coordinated Plan Comments (PDF)

Minneapolis development and economic equity: Upper Harbor Terminal can be a national model Star Tribune op-ed by Mayor Jacob Frey and City Councilmember Phillipe Cunningham, Feb. 18, 2019

Revamp the Upper Harbor Project Star Tribune op-ed, June 22, 2020

Timeline: A history of North Minneapolis Upper Harbor Terminal Site NPR, Feb. 19, 2020

money.power.land.solidarity Podcast by community organizer Jake Virden about the Upper Harbor Terminal

Key Dates: Line 3

2014 Enbridge decides it needs to replace the existing Line 3 pipeline and begins planning with local, state and federal agencies.

September 2017 The MN Department of Congress issues a statement saying that Enbridge has not established a need for Line 3.

June 2018 The Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (PUC) unanimously votes to approve the certificate of need for Line 3.

October 2018 The PUC issues the route permit. The new pipeline corridor goes around Fond Du Lac reservation instead of through it.

June 2019 The Court of Appeals rules that Enbridge’s Environmental Impact Statement was insufficient because it doesn’t address the risk of an oil spill in the Lake Superior Watershed.

March 23, 2020 Court of Appeals rescinds an air quality permit

November 30, 2020 The MPCA grants the final water-crossing permit, and Enbridge is approved to begin construction.

December 1, 2020 Pipeline construction begins in earnest.

December 25, 2020 Two Ojibwe bands and two nonprofits file a complaint in a US District Court in Washington DC. They challenge the validity of a water quality permit issued by the US Army Corps of Engineers, and request a stay on construction until all the appeals are resolved.

Key Dates: PolyMet

May 2000 PolyMet applies for the rights to a cluster of minerals known as the NorthMet deposit

2010 PolyMet submits its first Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), which is rejected by the EPA because of concerns about long-term water-quality impacts

2014 A second draft, completed in collaboration with the MN Department of Natural Resources, the US Forest Service, and the Army Corps of Engineers, is submitted to the EPA for review. The EPA says it contains “insufficient information” but gives it the lowest passing grade. PolyMet begins acquiring permits.

2018 The project is fully permitted, but only briefly; 10 months later, the MN Court of Appeals reverses two dam permits

Key Dates: Twin Metals

2011 The company begins studying the site, but is immediately confronted with uncertainty when, in 2012, the Obama administration denies their lease renewal and initiates a study that would likely have resulted in a ban on sulfide-ore mining on federal lands.

2016 The Trump Administration shelves the study.

2019 Twin Metals officially begins their environmental review

2020 President Trump loosens mining regulation during Covid-19.

December 2020 MN State Representative Betty McCollum introduces the Boundary Waters Protection and Pollution Prevention Act, which would withdraw 234,238 miles of federal land and water in the Rainy River Watershed from mineral leasing.

Key Dates: Upper Harbor Terminal

2015 Minneapolis permanently closes the lock and dam at St. Anthony Falls, making the Upper Harbor Terminal obsolete.

2017 The City of Minneapolis enters into an exclusive rights agreement with real estate firm United Properties. First Avenue is given the go-ahead to build a music venue on the property.

Summer 2018 Activists and McKinley residents come together to form the Northside Eco-Harbor Co-Creation Team. They begin their own public outreach process and mobilize to delay the city council’s vote on the concept plan several times.

Early 2019 The Minneapolis City Council appoints the Collaborative Planning Committee to give community members a seat at the table. Two community members resign, saying the committee is not taking their concerns seriously.

March 2019 After pressure from activists, the concept plan is passed with amendments that would consider holding the land in public trust and signing a community benefits agreement (CBA).

January 2021 After pressure from the Northside environmental group Community Members for Environmental Justice, the City of Minneapolis announced that the Council would delay the vote on the plan until an environmental review is completed.

Mac in the News

Young Minnesotans find ‘calling’ leading Line 3 pipeline protests Sasha Lewis-Norelle ’21 was interviewed for this Star Tribune article from Feb. 23, 2021

‘A Tangible Way to Fight for the World I Want to Live In’: Water Protector Arrested After Blockading Line 3 Pipe Yard from Common Dreams, Dec. 28, 2020: Senior Emma Harrison quoted

Line 3: Not Just Another Pipeline New York Times op-ed (via Star Tribune) by Louis Erdrich that cites Professor Jim Doyle’s research

Line 3 proposal: yet another abuse against Native Americans Minn Post op-ed by Christine McCormick ’22, Environmental Studies major

Research

Mining Futures Research by Professor Roopali Phadke with student assistants Ari Jaheil, Betsy Schein, Martin Moore, Garrett Eichhorn and Kaitlyn Lindaman. Funded by the National Science Foundation.

The Injustice and Opposition of Enbridge’s Line 3 Replacement Project by CJ Denney ’23, fall of 2020

Get Involved

- Be trained to scout the pipeline, submit observations to public log with WatchTheLineMN.org

- Support Indigenous Media Makers

- Donate funds for supplies for Water Protectors to STOP LINE 3

- Participate in frontlines resistance – Landing site for allies traveling to Palisade, MN

- Attend pipeline resistance team meetings with MN 350

- Write your representative in support of Representative McCollum’s Bill HR 5598 to protect the Boundary Waters Wilderness

- On-ramps for the movement to Stop Line 3

- How to write a letter to the editor presentation

- Contact Anna Kleven ’21, Environmental Justice Leader in Service, Community Engagement Center at [email protected] to learn more about how to get involved, and sign up for her student newsletter.

Nonprofits Active in MN

Line 3

- Giniw Collective Facebook, Instagram

- Gitchigumi Scouts Facebook

- #StopLine3 Website, Facebook, Instagram

- Honor the Earth Website, Facebook, Instagram

- MN350 Pipeline Resistance Team

- Interfaith Power and Light (MNIPL)

Mining

Upper Harbor Terminal

Questions or Comments?

Questions or Comments?

Have questions, comments, or feedback about what you’ve read on this page? We’d like to hear from you! Please email [email protected].